Analytical Methods

for Lawyers

v Idea of the Course

¯ Brief survey of lots of areas useful to lawyers

¯ Many of which could be a full course--my L&E

¯ Enough so that you won't be lost when they come up, and É

¯ Can learn enough to deal with them if it becomes necessary.

v Mechanics

¯ Reading is important

¯ Discussion in class

¯ Homework to be discussed but not graded--way of testing yourself

¤ Prefer handout hardcopy or on web page? URL on handout

¯ Midterm? First time.

v

Topics

¯

Decision Analysis

¯

Game Theory

¯

Contracting: Application of Ideas

¯

Accounting.

¯

Finance

¯

Microeconomics.

¯

Law and Economics.

¯

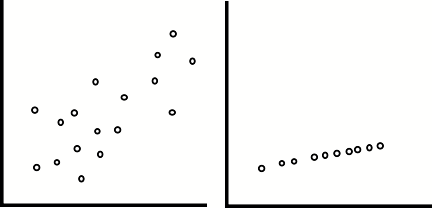

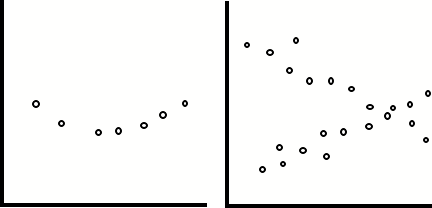

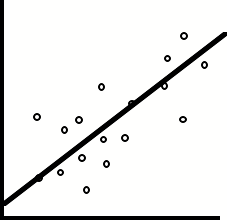

Statistics.

¯ Multivariate

Statistics: Untangling one out of many causes. Death penalty

v First Topic:

Decision Analysis

¯ Way of

formally setting up a problem to make it easier to decide

¯ Typically

¤ Make a

choice.

¤ Observe the

outcome, depends partly on chance

¤ Make another

choice.

¤ Continue

till the end, get some cost or benefit

¤ Want to know

how to make the choices to maximize benefit or minimize cost

¯ Simple

Example: Settlement negotiations

¤ Accept

settlement (known result) or go to trial

¤ If trial win with some probability and

get some amount, or lose and have costs

¤ Compare settlement offer to average

outcome at trial, including costs.

¯ Fancy example: Hazardous materials

disposal firm

¤ You suspect employees may have cut some

corners, violated disposal rules

¤ First choice: Investigate or don't.

á

If you

don't, probably nothing happened (didn't violate or don't get caught)

á

If you do,

some probability that you discover there is a problem. If so É

¤ Conceal or report to EPA

á

If you

conceal, risk of discovery--greater than at previous stage (whistleblowers)

á

If you

report, certain discovery but lower penalty

¯ In each case, how do you figure out what

to do? Two parts:

¤ If you knew all the probabilities and

payoffs, how would you decide (Decision Analysis)

¤ What are the probabilities and payoffs,

and how do you find them?

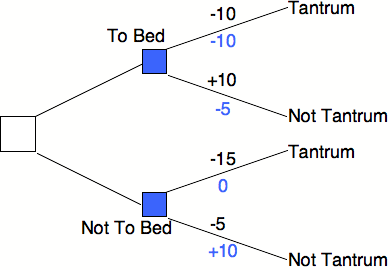

¯ Simple case again: Assuming numbers

¤ First pass

á

Settlement

offer is $70,000

á

Trial cost

is $20,000

á

Sure to win

á

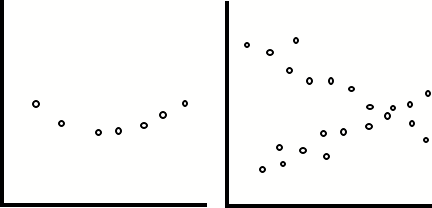

Tree

diagram

á

Lop off

inferior branch--easy answer

¤ Second pass: As above, but 60% chance of

winning

á

Square for

decision, circle for chance node

á

On average,

trial gives you $40,000

á

Is that the

right measure?

á

If so,

inferior. Lop off that branch

á

Settle

¤ Risk aversion

á

If you are

making similar decisions many times, expected value.

á

If once,

depends on size of stakes.

¯ Where do the numbers come from?

¤ Alternatives: Think. Talk to client,

colleagues, É Think through

alternatives.

á

Partly your

professional expertise

á

Forces you

to think through carefully what the alternatives are.

¤ Probabilities

á

Might have

data--outcome of similar cases in the past. Audit rate.

á

Generate

it--mock trial. Hire an expert.

á

By

intuition, experience. Interrogate. What bets would I accept?

¤ Payoffs

á

Include

money--costs, profits, fines, É Past cases, experts, É .

á

Reputational

gains and losses

á

For an

individual, moral gains and losses? Other nonpecuniary?

¯ Sensitivity analysis

¯ (Land Purchase Problem?)

¯ Is ethics relevant?

¤ Criminal trial--does it matter if you

think your client is guilty?

¤ EPA--does it matter that concealing may

be illegal. Immoral?

á

What if not

looking for the problem isn't illegal, but É

á

Finding and

concealing is?

v

Query re Becca

v Mechanics

¯ Office Hours

handout

¯ Everyone

happy with doing stuff online?

v Review:

Points covered

¯ Basic

approach

¤ Set up a

problem as

á

Boxes for choices

á

Circles for chance outcomes

á

Lines joining them

á

Payoffs, + or -, and probabilities.

¤ Calculate

the expected return from each choice, starting with the last ones

á

Since the payoff from one choice

á

May depend on the previous choice or chance.

¤ If one

choice has a lower payoff than an alternative at the same point, lop that

branch

¤ Work right

to left until you are left with only one series of choices.

¯ Complications

¤ Expected

return only if risk neutral

¤ You have to

work out the structure, with help from the client and others

¤ Estimate the

probabilities, and É

¤ Payoffs, not

all of which are in money.

¯ Sensitivity

analysis to find out whether the answer changes if you change your estimates.

v Handout

problems

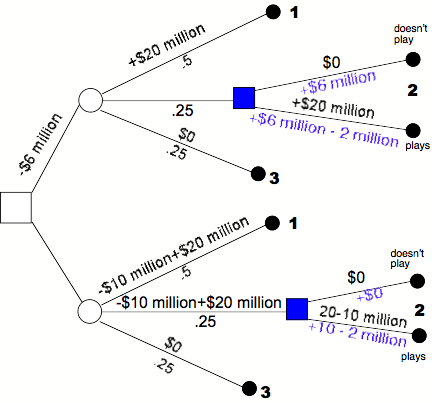

¯ Settle or go

to trial

¯ Which

contract to offer

¤ Easy answer

for the team

¤ Note that we

have implicitly solved the player's problem too.

á

Upper contract, if he has back pain, playing costs him $2 million,

gets him nothing, not playing neither costs nor gets, so don't play

á

Lower contract, if he has back pain, playing costs him $2 million,

gets him $10 million. Not playing gets and costs nothing. So he plays.

¤ Note also a

third option, that we didn't mention--no contract.

á

Better than the first

á

Could change the numbers to make it better than the second

á

Demonstrating that one has to figure out the structure of the

problem.

v Questions?

v More book

problems

¯ Land

purchase problem

v

v Game Theory

Intro: Show puzzling nature by examples

¯ Bilateral monopoly

¤ Economic case--buyer/seller, union/employer

¤ Parent/child case

¤ Commitment strategies

á

In economic

case

á

Aggressive

personality.

1/17/06

v Move to front of the room

v Strategic Behavior: The Idea

¯ A lot of what we do involves optimizing

against nature

¤ Should I take an umbrella?

¤ What crops should I plant?

¤ How do we treat this disease or injury?

¤ How do I fix this car?

¯ We sometimes imagine it as a game against

a malevolent opponents

¤ Finagle's Law: If Something Can Go Wrong,

It Will

¤ "The perversity of inanimate

objects"

¤ Yet we know it isn't

¯ But consider a two person zero sum game,

where what I win you lose.

¤ From my standpoint, your perversity is a

fact not an illusion

¤ Because you are acting to maximize your

winnings, hence minimize mine

¯ Consider a non-fixed sum game--such as

bilateral monopoly

¤ My apple is worth nothing to me (I'm

allergic), one dollar to you (the only customer)

¤ If I sell it to you, the sum of our gains

is É ?

¤ If bargaining breaks down and I don't

sell it, the sum of our gains is É

?

¤ So we have both cooperation--to get a

deal--and conflict over the terms.

¤ Giving us the paradox that

á

If I will

not accept less than $.90, you should pay that, but É

á

If you will

not offer more than $.10, I should accept that.

¤ Bringing in the possibility of bluffs,

commitment strategies, and the like.

¯ Consider a many player game

¤ We now add to all the above a new element

¤ Coalitions

¤ Even if the game is fixed sum for all of

us put together

¤ It can be positive sum for a group of

players

¤ At the cost of those outside the group

v Ways of representing a game

¯ Like a decision theory problem

¤ A sequence of choices, except that now

some are made by player 1, some by player 2 (and perhaps 3, 4, É)

¤ May still be some random elements as well

¤ Can rapidly become unmanageably

complicated, but É

¤ Useful for one purpose: Subgame Perfect

Equilibrium

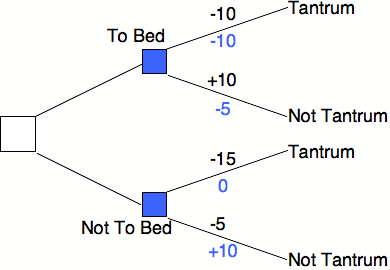

¤ Back to our basketball player--this time

a two person game

¤ But É Tantrum/No Tantrum game

¤ So Subgame Perfect works only if

commitment strategies are not available

¯ As a strategy matrix

¤ Works for all two player games

¤ A strategy is a complete description of

what the player will do under any circumstances

¤ Think of it as a computer program to play

the game

¤ Given two strategies, plug them both in,

players sit back and watch.

¤ There may still be random factors, but É

¤ One can define the value of the game to

each player as the average outcome for him.

¯ Dominant Solution: Prisoner's Dilemma as

a matrix

¤ There is a dominant pair of

strategies--confess/confess

á

Meaning

that whatever Player 1 does, Player 2 is better off confessing, and

á

Whatever Player

2, does Player 1 is better off confessing

á

Even though

both would be better off if neither confessed

|

|

Baxter |

||

|

Confess |

Deny |

||

|

Chester |

Confess |

10,0 |

0,15 |

|

Deny |

15,0 |

1,1 |

|

¤ How to get out of this?

á

Enforceable

contract

¬ I won't confess if you won't

¬ In that case, using nonlegal mechanisms

to enforce

á

Commitment

strategy--you peach on me and when I get out É

¯ Von Neumann Solution

¤ Von Neumann proved that for any 2 player

zero sum game

¤ There was a pair of strategies, one for

player A, one for B,

¤ And a payoff P for A (-P for B)

¤ Such that if A played his strategy, he

would (on average) get at least P whatever B did.

¤ And if B played his, A would get at most

P whatever he did

¯ Nash Equilibrium

¤ Called that because it was invented by

Cournot, in accordance with Stigler's Law

á

Which holds

that scientific laws are never named after their real inventors

á

Puzzle: Who

invented Stigler's Law?

¤ Consider a many player game.

á

Each player

chooses a strategy

á

Given the

choices of the other players, my strategy is best for me

á

And

similarly for everyone else

á

Nash

Equilibrium

¤ Driving on the right side of the road is

a Nash Equilibrium

á

If everyone

else drives on the right, I would be wise to do the same

á

Similarly

if everyone else drives on the left

á

Multiple

equilibria

¤ One problem: It assumes no coordinated

changes

á

A crowd of

prisoners are escaping from Death Row

á

Faced by a

guard with one bullet in his gun

á

Guard will

shoot the first one to charge him

á

Standing

still until they are captured is a Nash Equilibrium

¬ If everyone else does it, I had better do

it too.

¬ Are there any others?

á

But if I

and my buddy jointly charge him, we are both better off.

¤ Second problem: Definition of Strategy is

ambiguous. If you are really curious, see the game theory chapter

in my webbed Price Theory

v Solution Concepts

¯ Subgame Perfect equilibrium--if it exists

and no commitment is possible

¯ Strict dominance--"whatever he does

É" Prisoner's Dilemma

¯ Von Neumann solution to 2 player game

¯ Nash Equilibrium

¯ And there are more

1/19/06

v A simple game theory problem as a lawyer

might face it:

You represent the

plaintiff, Robert Williams, in a personal injury case. Liability is fairly

clear, but there

is a big dispute over damages. Your occupational expert puts the plaintiffÕs

expected future losses at $1,000,000, and the defendantÕs expert estimates the

loss at only $500,000. (Pursuant to a pretrial order, each side filed

preliminary expert reports last month and each party has taken the deposition

of the opposing partyÕs expert.) Your experience tells you that, in such a

situation, the jury is likely to split the difference, awarding some figure

near $750,000.

The deadline for

submitting any further expert reports and final witness lists is rapidly

approaching. You

contemplate hiring an additional expert, at a cost of $50,000. You suspect that

your additional expert will confirm your initial expertÕs conclusion. With two

experts supporting your higher figure and only one supporting theirs, the

juryÕs award will probably be much closer to $1,000,000 — say, it would

be $900,000.

You suspect,

however, that the defendantÕs lawyer is thinking along the same lines. (That

is, they could

find an additional expert, at a cost of about $50,000, who would confirm their

initial expertÕs figure. If they have two experts and you have only one, the

award will be much closer to $500,000 — say, it would be $600,000.)

If both sides hire

and present their additional experts, in all likelihood their testimony will

cancel out,

leaving you with a likely jury award of about $750,000. What should you advise

your client with regard to hiring an additional expert?

Any other ideas?

Set it up as a

payoff matrix

If neither hires

an additional expert, plaintiff receives $750,000 and defendant pays $750,000?

If plaintiff

hires an additional expert, plaintiff receives $850,000 and defendant pays

$900,000

If defendant

hires an additional expert, plaintiff receives $600,000 and defendant pays

$650,000?

If both hire

additional experts, plaintiff receives $700,000 and defendant pays $800,000?

|

|

Defendant: Doesn't hire |

Defendant: Hires |

|

Plaintiff: Doesn't Hire |

750, -750 |

600, -650 |

|

Plaintiff: Hires |

850, -900 |

700, -800 |

What does

Plaintiff do?

What does Defendant

do?

What is the

outcome?

Can it be

improved?

How?

v Game Theory: Summary

¯ The idea: Strategic behavior.

¤ Looks like decision theory, but

fundamentally different

¤ Because even with complete information,

it is unclear

á

What the

solution is or even

á

What a

solution means

¤ With decision theory, there is one person

seeking one objective, so we can figure out how he can best achieve it.

¤ With game theory, there are two or more

people

á

seeking

different objectives

á

Often in

conflict with each other

¤ A solution could be

á

A

description of how each person decides the best way to play for himself or

á

A

description of the outcome

¯ Solution concepts

¤ Subgame perfect equilibrium

á

assumes no

way of committing

á

No

coalition formation

¬ In the real world, A might pay B not to

take what would otherwise be his ideal choice--

¬ because that will change what C does in a

way that benefits A.

¬ One criminal bribing another to keep his

mouth shut, for instance

á

But it does

provide a simple way of extending the decision theory approach

¬ To give an unambiguous answer

¬ In at least some situations

¬ Consider our basketball player problem

¤ Dominant strategy--better against everything. Might not

exist in two senses

á

If I know

you are doing X, I do Y—and if you know I am doing Y, you do X. Nash

equilibrium. Driving on the right. The outcome may not be unique, but it is

stable.

á

If I know

you are doing X, I do Y—and if you know I am doing Y, you don't do X.

Unstable. Scissors/paper/stone.

¤ Nash equilibrium

á

By freezing

all the other players while you decide, we reduce it to decision theory for

each player--given what the rest are doing

á

We then

look for a collection of choices that are consistent with each other

¬ Meaning that each person is doing the

best he can for himself

¬ Given what everyone else is doing

á

This assumes

away all coalitions

¬ it doesn't allow for two ore more people

simultaneously shifting their strategy in a way that benefits both

¬ Like my two escaping prisoners

á

It also

ignores the problem of how to get to that solution

¬ One could imagine a real world situation

where

¯ A adjusts to B and C

¯ Which changes B's best strategy, so he

adjusts

¯ Which changes C and A's best strategies É

¯ Forever É

¬ A lot of economics is like this--find the

equilibrium, ignore the dynamics that get you there

¤ Von Neumann solution aka minimax aka saddlepoint aka É.?

á

It tells

each player how to figure out what to do, and É

á

Describes

the outcome if each follows those instructions

á

But it

applies only to two person fixed sum games.

¤ Von Neumann solution to multi-player

game (new)

á

Outcome--how

much each player ends up with

á

Dominance:

Outcome A dominates B if there is some group of players, all of whom do better

under A (end up with more) and who, by working together, can get A for

themselves

á

A solution

is a set of outcomes none of which dominates another, such that every outcome

not in the solution is dominated by one in the solution

á

Consider,

to get some flavor of this, É

¤ Three player majority vote

á

A dollar is

to be divided among Ann, Bill and Charles by majority vote.

¬ Ann and Bill propose (.5,.5,0)--they

split the dollar, leaving Charles with nothing

¬ Charles proposes (.6,0,.4). Ann and

Charles both prefer it, to it beats the first proposal, but É

¬ Bill proposes (0, .5, .5), which beats

that É

¬ And so around we go.

á

One Von

Neumann solution is the set: (.5,.5,0), (0, .5, .5), (.5,0,.5) (check)

á

There are

others--lots of others.

¤ Other approaches to many player games

have been suggested, but this is enough to show two different elements of the

problem

á

Coalition

formation, and É

á

Indeterminacy,

since one outcome can dominate other which dominates another which É .

¤ Almost enough to make you appreciate Nash

equilibrium, where nobody can talk to anybody so there is no coalition

formation.

v Applied Schelling Points

¯ In a bargaining situation, people may end

up with a solution because it is perceived as unique, hence better than

continued (costly) bargaining

¤ We can go on forever as to whether I am

entitled to 61% of the loot or 62%

¤ Whether to split 50/50 or keep bargaining

is a simpler decision.

¯ But what solution is unique is a function

of how people think about the problem

¤ The bank robbery was done by your family

(you and your son) and mine (me and my wife and daughter)

¤ Is the Schelling point 50/50 between the

families, or 20% to each person?

¤ Obviously the latter (obvious to me--not

to you).

¯ It was only a two person job--but I was

the one who bribed a clerk to get inside information

¤ Should we split the loot 50/50 or

¤ The profit 50/50--after paying me back

for the bribe?

¯ In bargaining with a union, when everyone

gets tired, the obvious suggestion is to "split the difference."

¤ But what the difference is depends on

each party's previous offers

¤ Which gives each an incentive to make

offers unrealistically favorable to itself.

¯ What is the strategic implication?

¤ If you are in a situation where the

outcome is likely to be agreement on a Schelling point

¤ How might you improve the outcome for

your side?

v Odds and Ends

¯ Prisoner's dilemma examples?

¤ Athletes taking steroids. Is it a PD?

¤ Countries engaging in an arms race

¤ Students studying in order to get better

grades?

¯ Is repeated prisoner's dilemma a

prisoner's dilemma?

¤ Suppose we are going to play the same

game ten times in succession

¤ If you betray me in round 1, I can punish

you by betraying in round 2

¤ It seems as though that provides a way of

getting us to our jointly preferred outcome—neither confesses.

¤ But É

¯ Experimental games

¤ Computers work cheap

¤ So Axelrod set up a tournament

á

Humans

submit programs defining a strategy for many times repeated prisoner's dilemma

á

Programs

are randomly paired with each other to play (say) 100 times

á

When it is

over, which program wins?

¤ In the first experiment, the winner was

"tit for tat"

á

Cooperate

in the first round

á

If the

other player betrays on any round, betray him the next round (punish), but cooperate

thereafter if he does (forgive)

¤ In fancier versions, you have evolution

á

Strategies

that are more successful have more copies of themselves in the next round

á

Which

matters, since whether a strategy works depends in part on what everyone else

is doing.

á

Some more

complicated strategies have succeeded in later versions of the tournament,

á

but tit for

tat does quite well

¤ His book is The Evolution of

Cooperation

v Threats, bluffs, commitment strategies:

¯ A nuisance suit.

¤ Plaintiff's cost is $100,000, as is

defendant's cost

¤ 1% chance that plaintiff wins and is

awarded $5,000,000

¤ What happens?

¤ How might each side try to improve the

outcome

¯ Airline hijacking, with hostages

¤ The hijackers want to be flown to Cuba

(say)

¤ Clearly that costs less than any serious

risk of having the plane wrecked and/or passengers killed

¤ Should the airline give in?

¯ When is a commitment strategy believable?

¤ Suppose a criminal tries to commit to

never plea bargaining?

¤ On the theory that that makes convicting

him more costly than convicting other criminals

¤ So he will be let go, or not arrested

v Moral Hazard

¯ This is really economics, not game

theory, but it's in the chapter

¯ I have a ten million dollar factory and

am worried about fire

¤ If I can take ten thousand dollar

precaution that reduces the risk by 1% this year, I

will—(.01x$10,000,000=$100,000>$10,000)

¤ But if the precaution costs a million, I

won't.

¯ insure my factory for $9,000,000

¤ It is still worth taking a precaution

that reduces the chance of fire by %1

¤ But only if it costs less than É?

¯ Of course, the price of the insurance

will take account of the fact that I can be expected to take fewer precautions:

¤ Before I was insured, the chance of the

factory burning down was 5%

¤ So insurance should have cost me about

$450,000/year, but É

¤ Insurance company knows that if insured I

will be less careful

¤ Raising the probability to (say) 10%, and

the price to $900,000

¯ There is a net loss

here—precautions worth taking that are not getting taken, because I pay

for them but the gain goes mostly to the insurance company.

¯ Possible solutions?

¤ Require precautions (signs in car repair

shops—no customers allowed in, mandated sprinkler systems)

á

The

insurance company gives you a lower rate if you take the precautions

á

Only works

for observable precautions

¤ Make insurance only cover fires not due

to your failure to take precautions (again, if observable)

¤ Coinsurance.

¤

¯ Is moral hazard a bug or a feature?

¤ Big company, many factories, they insure

á

Why? They

shouldn't be risk averse

á

Since they

can spread the loss across their factories.

¤ Consider the employee running one factory

without insurance

á

He can

spend nothing, have 3% chance of a fire

á

Or spend $100,000, have 1%--and make

$100,000 less/year for the company

á

Which is it

in his interest to do?

v Adverse Selection—also not really

game theory

¯ The problem: The market for lemons

¤ Assumptions

á

Used car in

good condition worth $10,000 to buyer, $8000 to seller

á

Lemon worth

$5,000, $4,000

á

Half the

cars are creampuffs, half lemons

¤ First try:

á

Buyers

figure average used car is worth $7,500 to them, $6,000 to seller, so offer

something in between

á

What

happens?

¤ What is the final result?

¯ How might you avoid this

problem—due to asymmetric information

¤ Make the information

symmetric—inspect the car. Or É

¤ Transfer the risk to the party with the

information—seller insures the car

¯ What problems does the latter solution

raise?

v To think about:

¯ Genetic testing is making it increasingly

possible to identify people at risk of various medical problems

¯ If you are probably going to get cancer,

or have a heart attack, and the insurance company knows it, insurance will be

very expensive, so É

¯ Some people propose that it be illegal

for insurance companies to require testing.

¯ What problems would that proposal raise?

1/24/06

v Genetic Testing:

¯ A. No Testing

¯ B. Customers can test; insurance

companies cannot condition rates on results

¯ Customers can test, insurance companies

can condition rates

¯ What happens?

v Contracts

¯ Why they matter

¤ A large part of what lawyers do is

drawing up and negotiating contracts

¤ In many different areas of the law

á

Employment

á

Partnerships

á

Sales

contracts

á

Contracts

between firms

á

Prenuptial

agreements and Divorce settlements É

¯ Why make a contract?

¤ Why deal with other people at all?

á

Because

there are gains to trade

á

The same

property may be worth more to buyer than seller

á

Different

people have different abilities

á

Specialization

and division of labor

á

Complementary

abilities

á

Risk

sharing

¬ An insurance contract not only transfers

risk

¬ It reduces it--via the law of large

numbers

á

Does a bet

due to different opinions count as gains from trade?

¤ A spot sale isn't much of a contract--why

anything else?

á

Because

performance often takes place over time

á

And the

dimensions of performance are more complicated than "seventeen bushels of

wheat."

á

Even a spot

contract might include details of quality--not immediately observable--and

recourse.

¯ Two Objectives in negotiating a contract

¤ Maximize the size of the pie

¤ Get as much of it as possible for your

client

¯ The second was covered in the previous

chapter

¤ If there is some surplus from the

exchange

á

Meaning

that you can both be better off with a contract

á

Than

without one

¤ Then you are in a bilateral monopoly

bargaining game

á

You are

both better off if you agree to a contract

á

But the

terms will determine how much of the gain each of you gets

¤ Where commitment strategies or control of

information might help

á

But at the

risk of causing bargaining breakdown

¬ Each of us is committed to getting at

least 60% of the gain, or É

¬ I have persuaded you that what you are

selling is only worth $10 to me, and it is worth $11 to you.

á

And the pie

goes into the trash

¯ This chapter is about the first--maximize

the size of the pie

¤ Any time you see a way of increasing the

size

¤ You can propose it, combined with a

change in other terms--such as price

¤ That makes both parties better off

¤ This point is central to the

chapter—if you are not convinced, we should discuss it now.

v Why incentives matter

¯ People often talk as if "more

incentive" was unambiguously good

¤ Gordon Tullock's auto safety device

¤ There is such a thing as too much

incentive

¤ What is the right incentive--for

anything?

¯ Consider a fixed price contract to build

a house

¤ Instead of spending $10,000 on roofing

material that lasts 20 years

¤ The builder spends $5,000 on material

that lasts 5 years

¤ After which the material must be replaced

at a cost of $12,000

¯ What is the sense in which this is a bad

thing?

¤ Compare to the case where the $5,000

material lasts 19 years.

¤ You want to set up the contract so he

won't use the cheap material in the first case, but É

¤ What about the second?

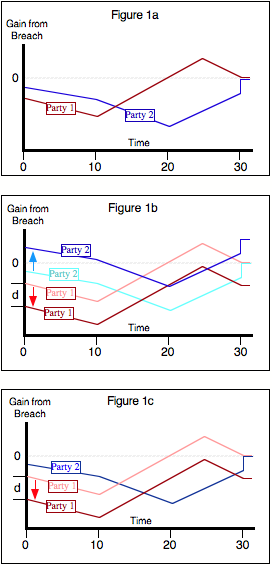

¯ How about the incentive not to breach a

contract?

¤ Should contracts ever be breached?

¤ When?

¤ How do you get that outcome?

¯ Enforceability and observeability

¤ Consider the marriage contract

á

Al-Tanukhi

story

á

Lots of

dimensions of performance are unobservable by an outside party

á

So a wife

who wants a divorce É .

á

You might

want to think about the general problem of marriage contracts

¬ Traditional: Divorce hard, gender roles

largely specified by custom

¬ Current: Divorce on demand, terms freely

negotiable day by day, mostly not enforceable

¬ Alternatives?

¬ What are the problems in designing a

marriage contract?

¬ We will return to that question

¤ Ideally, the contract specifies terms

that are observable

¤ Not always a sharp distinction

á

Sometimes performance

can be imperfectly observed--how well is this house built?

á

And one

might specify how to observe it--name the expert body whose standards you are

agreeing to.

¤ A second enforceability problem--what if

a party breaches and can't pay the damages?

¯ Reputation

¤ In today's discussion, we implicitly

assume that the only constraint on both parties is the contract itself

¤ In many cases that's not realistic. One

or both parties is a repeat player, and wants not only to stay out of court but

to keep customers and get more.

¤ We will return to that question later,

since it is relevant to how to structure contracts.

v Production Contracts—building a

house.

¯ One party pays the cost, gets the house,

the other builds it.

¯ Cost-plus or flat fee: Advantages and

disadvantages

¤ Why is there a "plus" in cost

plus?

á

If one

contractor will do the job for cost+$10,000, why won't another do it for

cost+$9,000?

á

Isn't the

"plus" something for nothing? $9,000 is better than zero.

¤ Is it "plus" or "plus

10%?"

¤ Why?

¯ Incentive to get inputs at the lowest

possible cost

¤ Flat fee: any savings goes to the contractor

á

So he wants

to minimize cost--including both price and his time and trouble

á

Which is

what you want him to do

á

Why do you

care about his time and trouble?

á

What would

happen if you set up the contract to force him to buy the input at the lowest

possible price (holding quality fixed--same brand of windows, say)? Imagine he

had to pay you a five thousand dollar penalty if you could show that,

somewhere, it was possible to buy an input for less than he paid?

¤ Cost plus: savings on price goes to you

á

But any

increase in time and trouble needed to get the lower price he pays

á

So he won't

try very hard to find a lower price

á

Even if it

would save you more than it costs him to do so

¤ Cost plus 10%?

á

Friedman's

rule for finding the men's room

á

And why it

sometimes doesn't work

¤ If you are using cost plus, how might you

control the problem?

¤ What are the problems you will face?

¯ Incentive to get inputs of the right

quality

¤ Do we always want the highest quality

inputs?

á

Do you only

eat at gourmet restaurants?

á

And buy the

highest quality car you can afford?

¤ Flat fee contract: Incentive of the

builder is É

á

To use the

least expensive inputs, whatever their quality

á

Because a

dollar saved is a dollar earned--for him

¤ Cost plus contract, he doesn't

care--extra quality comes out of your pocket

¤ Cost plus 10%?

¤ With a flat fee contract, how might you

try to control the problem?

¤ What problems arise in doing so?

¯ Uncertainty:

¤ Renegotiating the contract

á

Your client

forgot something important--try to prevent that in advance

á

Something

important changed.

á

You are

stuck in a bilateral monopoly with the builder

¬ The bargaining range is bounded on one

side by the terms of the initial contract--if he fulfills it he is in the clear

¬ And on the other side by the most you are

willing to pay for the change

¬ Which might be expensive

á

You could

include terms for changes in the contract

¬ Will that be easier with flat fee, cost

plus, cost plus 10%?

¬ Think about it from the builder's

standpoint.

¤ Risk bearing

á

What if

something changes that greatly increases the cost?

¬ Under flat fee, the builder swallows the

loss

¬ Under cost plus, you do

á

What if

something changes that greatly lowers the value to you?

¬ You contract to have land cleared and a

new factory built

¬ In 1929

¬ Risk allocation depends on the

contractual terms for breach

¬ Or on negotiation--again, with a

potential holdout problem

á

Why does

risk bearing affect the size of the pie?

¬ Because different parties have different

abilities to bear risk

¬ Because poor contract terms or bargaining

breakdown might lead to a smaller pie--the land gets cleared, the factory

built, and it sits empty until 1942.

Electronic Equipment Service Contract

Global

Consolidated Industries (GCI) has for years had an in-house electronic

equipment maintenance department. It has been responsible for providing

maintenance (such as periodic cleaning and lubrication of moving parts) and

repair (fixing machines when they break down) on thousands of printers,

photocopy machines, FAX machines, scanners, and so forth. The experience, in a

word, has been a disaster. On most days, secretaries can be seen running from

floor to floor and pushing in line to use other machines when theirs are

inoperative. Even the CEO is often heard screaming about memos being late,

meetings having to be rescheduled, and other headaches caused by out-of-order

equipment.

GCI has

decided that it is time to contract out for these services. As a member of

GCIÕs general counselÕs office, you have been called in to participate in the

contract negotiations with the outside service provider, Reliable Response

Repair (RRR).

RRR has

offered two contracts for your consideration. Under one contract, RRR receives

a flat rate per machine each contract year. (For example, there is a $200 per

year charge for a standard, mid-size photocopy machine.) Under this

arrangement, RRR is obligated to provide all necessary maintenance and to

repair broken-down machines promptly.

Under the

second contact, RRR is paid $75 per hour (plus parts) for all maintenance and

repair services. Under this arrangement as well, RRR is obligated to provide

all necessary maintenance and to repair broken-down machines promptly.

Explain the

pros and cons of each of the two contracts. Which seems best? Can you think of

additional terms that would improve it?

v

What is RRR's

incentive to do a good job of maintaining and fixing the machines under either

contract?

v

To do it

promptly?

v

What are GCI's

incentives under each contract? Why might RRR care about that?

v

Flat rate:

¯ RRR incentives

¤

Incentive to

maintain if it is cheaper than fixing

¤

Incentive to do

a good job of fixing, since if not they have to come back

¤

Promptness?

Only to the extent you can enforce that term

á

So you may want

to define it more precisely

á

Must show up

within 2 hours, fix within 4, or É

á

Penalty based

on how many hours machines are down each year, or É

á

Bonus for less

than 6 hours down time per machine

¤

Risk?

á

Very little

risk to GCI—they know how much they will pay

á

All of the risk

is on RRR—what if a machine has problems and keeps giving trouble?

á

But GCI is big

enough so that such effects should average out

¯ GCI incentives:

¤

Why do you

worry about those?

¤

GCI has little

incentive to take good care of machines, train people well, control whatever

inputs they provide that affect the chance of breakdown

¤

Little

incentive to hold down RRR's cost by, say, not using machines heavily at two in

the morning, or only asking for a technician to be sent when the problem is

serious

¤

GCI has reduced

incentive to buy good quality machines

á

So the contract

might specify machines presently on site, which RRR can inspect in advance

á

Or specify what

brands and models of new purchases are covered

v

Per hour:

¯ RRR incentives

¤

If per hour is

more than their real cost, a serious problem

á

Why maintain

when you get paid to fix?

á

Why fix well

when you get paid to come back?

¤

If per hour is

at their real cost, still have to monitor to make sure they are really working

that many hours

¤

Promptness

still a problem as above.

¯ GCI Incentives

¤

GCI now has an

incentive to buy good machines

¤

To take good

care of the machines

¤

Only to call a

tech when really needed

¤

And RRR might

charge more at 2 A.M. (modification of terms)

¯ Question: Does GCI have to use RRR under this

contract?

¤

If not, they

can use competition or the threat of it to control some of these problems, but

É

¤

A problem if

RRR is hiring extra maintenance personnel specifically to deal with GCI

repairs.

v

What if quality

of repair affects machine lifetime?

¯ Either way, RRR has little incentive to do a

good job in that dimension

¯ Perhaps GCI should lease the machines from

RRR, with repairs and maintenance included in the terms.

v

Perhaps what we

want is some of the cost on each party

¯ Per hour payment low enough to give RRR an

incentive to maintain machines, fix

them right, but É

¯ High enough to give GCI an incentive to do

what it easily can to avoid breakdowns.

¯ The same principle as coinsurance.

¤

Neither party

bears the full cost, so neither has as much incentive to prevent the problem as

we would like, but É

¤

Each bears

enough of the cost to make it in its interest to take most of the precautions

that ought to be taken.

Musician and Nightclub

Booking Arrangement

Your client, Jerry the Jazz musician, is becoming increasingly

well-known in the region. He has recently been offered a booking arrangement by

the Nightowl nightclub, the ritziest jazz bar in the city, for Tuesday nights.

They propose paying him $500 per appearance plus 10% of house profits. Because

they want to have the opportunity to use other musicians for variety, taking

advantage of out-of-town players who pass through, they are only willing to

guarantee Jerry 26 Tuesday night appearances over the course of the year. They

would give him one weekÕs notice with regard to each Tuesday, and he would be

obligated to appear when called.

Jerry tells you that he finds this offer attractive because it

would give him some stability in his income, something he has never had before.

On the other hand, he does not like the idea that the arrangement would

preclude his doing any other gigs on a Tuesday night (or out-of town gigs on

Mondays or Wednesdays); given his increasing reputation, he occasionally gets

great one-shot offers.

How do you advise Jerry regarding his contract negotiations with

Nightowl?

v

Gains

from trade

¯

Jerry

and Nightowl both reduce uncertainty

¯

Appearing

regularly at Nightowl probably benefits both

v

Problems

that might be fixable:

¯

Jerry

wants flexibility for out of town gigs

¯

How

to reduce the cost of that to Nightowl?

¤

If

he gives them a month advance notice, might be able to fill in

á

They

only plan to use him half the Tuesdays

á

Still

some cost--there might not be anybody good in town

á

But

perhaps less than the benefit to Jerry

¤

What

if he can get off if he finds a substitute?

á

How

do we define an adequate substitute?

á

Someone

they have hired before?

á

Someone

from a pre-agreed list?

¤

What

if he agrees to play a different day when he isn't there Tuesday?

¤

What

if he can take off a fixed number of Tuesdays by one month advance notice?

á

Hypothetical

numbers

á

Jerry

wants the right to block out 5 Tuesdays, a month in advance

á

Nightowl

thinks it costs them $400/Tuesday

¬

Hassle

of finding a replacement

¬

Risk

of lower quality

¬

Disappointment

of Tuesday customers who are fans of Jerry's.

á

Jerry

offers to accept $400 instead of 500 per appearance in exchange

á

Saves

Nightowl $100x26 Tuesdays=$2600, so they are better off

á

Jerry can

make $1000 more for out of town gigs, so gains $5000, loses $2600, so he is

better off too

v

Other

issues

¯

If Jerry

has the option, he might choose big nights--New Year's Eve--since he is getting

the same fee for every night from Nightowl, could get more elsewhere.

¤

How might

we solve that?

¤

Pay him

more for specified big nights?

¤

Or

specified big nights he doesn't have the option of taking off?

¤

Or, when he

notifies them, they bargain with him?

¯

Breach:

Under the initial contract, what if he accepts a Tuesday gig and then Nightowl

wants him that Tuesday?

¤

Liquidated

Damages? What does the contract say?

¤

What if he

is sick and can't play?

¤

Can Nightowl

tell the difference? Depends how far away the gig is?

¤

Breach

terms another way of getting flexibility

á

Liquidated

damages of $300 if be backs out with a month notice

á

$500 a

week's nnotice

á

$2000 if he

just doesn't show up

á

How should

we set the damages?

á

How about

calling in sick?

¤

Negotiation

another way of getting flexibility

á

Gets an

invitation for an out of town gig

á

Asks

Nightowl if they need him that night

á

If they do,

starts bargaining

á

Assymetric

information? How is it in Nightowl's interest to act?

á

Can Jerry

tell?

v

Incentive

issues

¯

For Jerry:

What are his incentives

¤

To do a

good job?

¤

To come

when he says he will?

¯

What are

Nightowl's incentives?

¤

To

advertise Jerry

¤

To run a

good club (why does he care?)

¤

To use him

often?

á

Should

there be different terms for other nights?

á

He isn't

committed--but doesn't get paid as much?

á

His time is

probably worth much less than $500 if he doesn't have a gig

v

Verifiability:

¯

Jerry gets

10% of profits--how measured?

¤

You are an

unscrupulous Nightowl owner--how do you hold down what you pay Jerry?

¤

Can he

tell?

¯

Are there

other ways of rewarding him related to how good a job he does?

¤

More easily

observed? Revenue--but also a bit tricky

¤

More

closely targetted on his contribution?

v

General

issues here are:

¯

Enlarging

the pie

¯

Via incentives

¯

Risk

bearing?

¯

Verifiability

of terms

State AG Litigation Contract

You are a lawyer

in the consumer protection division of the state attorney generalÕs office.

Preliminary investigations as well as some undercover stories in the press

reveal the possibility of a major billing scandal involving the health care

industry. Following the growing number of states who have recently pursued such

claims and the recent huge success in tobacco litigation, it is proposed to

bring suit against a number of firms. The total damages claim is for hundreds

of millions of dollars, possibly more than a billion.

Your office, however, has only four

attorneys, many of whom are quite busy on other matters. Therefore, it is

agreed to hire an outside firm that specializes in large-scale litigation,

probably one of those super-successful plaintiffsÕ boutique firms. Many of them

have already expressed interest and some have been interviewed.

Two further notes.

First, although this novel litigation strategy has the potential to be

extremely lucrative, it will also be expensive, requiring that millions of

dollars worth of lawyersÕ and expertsÕ time be invested up front. Second, the

office is worried about the possible political fallout of making fee payments

to outside lawyers that prove embarrassingly large.

Advise your

department head on the compensation scheme that should be used in the contract

with the outside firm. Focus on the form of the compensation scheme and any

closely related matters. In preparing your advice, be sure that you do each of

the following:

Describe different

ways that the firm could be compensated.

Identify the major

pros and cons of each approach.

Discuss how, if at

all, any negatives of a given approach may be mitigated.

|

Compensation

Scheme |

Incentives |

Risk |

Political, Other |

|

Flat Fee |

|

|

|

|

Hourly |

|

|

|

|

Contingent Fee |

|

|

|

v

Flat Fee

¯

Incentives

¤

No

financial incentive for lawyers to win

¤

Possible

reputational incentive

¤

How well

can a small AG's office monitor the lawyers?

¤

Can you

control how hard they try by contract?

¯

Risk

¤

None on

payment for law firm

¤

But they

bear all the risk of costs

¤

Who is more

risk averse?

¯

Political

¤

No risk of

stories on huge fee payment, but É

¤

If the case

fails, agency looks bad--money for nothing

v

Cost-Plus

(hourly)

¯

Incentives

¤

To spend

too much time if rate is higher than real cost of time to firm

á

Too little

if rate is lower, but É

á

Less of a

problem than the previous case, where hourly rate is zero.

¤

Can you

verify

á

Hours

actually worked

á

Quality of

work. Who do they assign, how hard does he try?

¤

Can you

control by contract?

¯

Risk

¤

All of the

revenue risk is born by the state

¤

And most of

the cost risk

¯

Political

¤

No risk of

huge payments for now work, but É

¤

Risk of

huge payments for no return

v

Contingent

Fee

¯

Incentives

¤

Firm wants

to win.

¤

How large a

fractional payout?

á

Higher

percentage, better incentives, but É

á

Less left

for the state

á

What about

100% and negative fixed fee?

¤

At anything

less than 100%, incentive still imperfect. Assume 50%.

á

If it costs

the firm $1000 to increase expected return by $1500, they won't do it.

á

So still

want some oversight

á

And hope

reputation helps.

¤

No

incentive for the firm to get relief other than a damage payment

¯

Risk

¤

Is being

shared between firm and state

¯

Political

¤

No risk of

large payment for no result

¤

But very large

amounts to lawyers if the suit is successful might be embarrassing

v

What is the

maximand?

¯

Suppose the

defendant is actually innocent

¯

The law

firm still wants to win

¯

Does the

state?

v

School

Gymnasium: Applying what we have learned.

¯

Flat fee or

Cost plus?

¤

The school

probably doesn't know enough to monitor a cost-plus contract

¤

And is

probably in a poor position to bear risk

¤

So flat fee

is probably better, but É

¯

Problems

with flat fee

¤

Maintaining

quality

á

Have to

specify a lot of details

á

School

doesn't have the expertise to do that, but É

á

Their

architect might.

á

Hire some

sort of expert to write the specs

¤

Making

changes

á

Question

your client carefully to keep later changes from being necessary

á

Perhaps

include in the contract that changes can be made on a cost plus basis

á

Or plan on

negotiating changes.

v

Arguments

in litigation

¯

The book

sketches the law and econ argument for enforcing the quality terms in a flat

fee contract

¤

Because

otherwise the builder has an incentive to degrade quality

¤

Even when

doing so costs you more than it saves him.

¯

Do you

think a judge would find that more or less convincing

¯

Than the

"good faith" sort of argument?

v

Principle/Agent

Contracts

¯

Lots of

varieties, including

¤

Construction

contracts we have been discussing

¤

Employment

contracts

¤

Lawyer/client

contracts--you are the agent.

¤

Is the

President the voters' agent?

¤

É

¯

Possible

forms

¤

Pay by

performance--did you sell a car? Win a case?

¤

Pay for

inputs--how many billable hours?

¤

Fixed-fee

¤

Combinations.

á

Employees

frequently get a fixed salary, plus É

á

Bonus for

specified accomplishments, by them or their unit or the firm, or É

á

Optional

bonus--Google example.

á

Your raise

next year is to some extent a "by performance" for this year

¯

Incentives:

How to make it in the interest of the agent to do what the principal wants

¤

What does

the principal want?

á

"To

win her lawsuit?"

á

At any

cost?

¤

Performance

based contracts give the agent an incentive

á

To achieve

the objective

á

If the

reward for doing so is greater than the cost of doing so

á

Suppose the

reward is 10% of the value of success

á

Will the

agent act as the principal would like?

á

What about

200%?

á

If all we

are concerned about is the right incentive, the reward should be É?

á

What are

the problems with this solution?

¬

It might

pay the agent too much.

¬

Consider a

store whose profit depends on ten different employees.

¬

How would

we solve that problem?

¬

The

solution might impose too much risk on the agents.

á

So there

are costs to the rule that gives the right incentive.

á

A further

problem is measuring output

¬

Consider

the President of a publicly traded company

¬

Perhaps

profits are low this year because of high research costs which will bear fruit

in five or ten years

¬

Or because

of problems facing the industry for which he is not responsible.

¬

Consider a

secretary or janitor or É . How do

you measure output?

á

One reason

to decentralize firms is to make this problem a little easier to solve

¬

We can

judge the output of the Buick division of GM better if it is run like a

separate company

¬

Of one

partner in a law firm if we can keep track of his accounts

¯

Input based

contract

¤

For

instance, paying an hourly wage

¤

Or billable

hours

¤

Gives the

agent an incentive on the measurable dimension of input

¤

But not on

other dimensions--how hard he works, for instance.

¯

Fixed fee

contract

¤

No

automatic incentive to do anything

¤

Make the

fixed fee for some measurable result (show up in court, etc.)

¤

Or have

some way of defining what inputs the fixed fee is buying, and monitoring them.

¤

May rely

heavily on reputation.

v

Risk

bearing

¯

Performance

based, risk born largely by the agent

¯

Input

based, principal bears risk of outcome, risk of wanting more inputs.

¯

Fixed fee,

principal bears risk of outcome, agent risk of costs.

v

Coffee

house manager employment contract

¯

Performance

based

¤

Do we have

to base it on the profits of the whole firm?

¤

Or is there

a better solution?

¤

What about

compromises to reduce the risk the manager bears?

¯

Input based

¤

Performance

depends on manager's inputs, but É

¤

Much of it

is qualitative, hard to measure, harder to prove to a court in case of dispute

¤

And the

quantitative--hours put it in--requires someone monitoring the manager

á

Which means

someone working in his coffee house

á

And so

partly dependant on him for promotion etc.

¯

Fixed

fee--flat salary

¤

Requires

monitoring of inputs and performance

¤

If unsatisfactory,

replace the manager

v

Joint

undertakings

¯

Include

¤

Partnership--such

as a law firm

¤

Joint

project by two firms--Apple and IBM, say

á

IBM

develops a new chip (G5, 60 nm)

¬

Apple makes

plans and promises based on it

¬

And Steve

Jobs eats crow when he still doesn't have his 3 Ghz desktop.

á

How might a

contract deal with this (don't know if it did)

¬

IBM

controls how hard they try

¬

And has

more information on what they can do, risks (not enough information, as it

turned out—everyone had more trouble with 60 nm than expected)

¬

So should

IBM be liable for Apple's losses?

¬

But Apple

is the one deciding what promises Steve makes, other decisions affecting amount

of loss.

¤

É

¯

Incentives

¤

Horizontal

division—between partners, allocating income by business brought in,

billable hours, É

¤

Functional

division—Apple and Motorola above.

¯

Risk

sharing

¤

May modify

"reward by output" within firm

¤

Partly

output, partly input, partly fixed

¯

What is

observable?

¤

Did IBM

make best efforts to develop?

¤

Could Intel

be used as benchmark?

¤

Did Apple act

to minimize loss due to failure of IBM to deliver?

v

Sale or

lease of property

¯

Quality

dimension

¤

Of property

as delivered

¤

And as

returned

¤

Inspect?

¤

Contractual

restrictions on use, subletting, É

¤

Security

deposit

á

Saves court

costs if property damaged,

á

Solves

judgement proof problem, but É

á

How do you

keep landlord from confiscating it if not damaged?

á

Raises the

general issue of structuring a contract wrt what happens if nobody goes to

court. Will return to that Thursday

¤

Damage in

delivery

á

Make the

party who has possession liable? Can best control

á

Or the

party who chooses third party to deliver

¯

Information

¤

What are

you obliged to tell?

¤

Treaty of

Paris, war of 1812, case.

¤

Poltergeist

case

¯

Who bears

the risk of the rented building burning down?

¤

Incentive—tenant

¤

Risk

spreading? Probably landlord.

v

Loan

¯

Risk of

bankruptcy,

¤

deliberate

or otherwise.

¤

"deliberate"

might include taking risks—heads I win, tails you lose.

¤

Control by

á

Security

interest in property—borrower can't sell it

á

Controls on

what borrower can do.

v

Resolving

disputes

¯

Some can be

avoided by anticipation, but É.

¤

There isn't

enough small print in the world to cover everything

¤

And events

may occur that you hadn't thought of.

¯

Damages for

breach

¤

Expectation

damages lead to efficient breach, inefficient reliance

¤

Liquidated

damages solve the problem—if damages can be estimated in advance.

v

Negotiating

the contract

¯

Try to

maximize the pie

¤

By offering

to buy improvements that help your side at a cost to the other

¤

To sell

improvements that help them at a cost to you

¤

To trade

¯

Try to

maximize your share—typically in the price

¤

While

remembering that if you ask for too much

¤

You risk

bargaining breakthrough

¤

And getting

nothing

v

China to

Cyberspace: Contracts without court enforcement

¯

An issue

for

¤

You—because

part of an attorney's job is staying out of court

á

Which you

do in part by designing contracts

á

Which it

isn't in either party's interest to try to get out of

á

Look at how

many contracts amount to the consumer signing away as many of his potential

claims as possible

¬

One explanation

is that it is that way to benefit the seller at the buyer's expense

¬

That seems

inconsistent with our analysis—any expense to the buyer will reduce what

he is willing to pay for the product

¬

Why might

this arrangement be in the interest of both? (stay tuned)

¤

Imperial

China—because legal system was almost entirely penal

á

You could

complain you had been swindled, ask the district magistrate to act

á

But you

couldn't actually sue and control the case

á

And the

legal system said almost nothing about contract law

¤

Cyberspace,

because

á

Hard to use

the legal system when dealings routinely cross jurisdictions

á

The

technology makes it possible to combine anonymity and reputation

¬

Public key

encryption as a way of maintaining anonymity

¬

And digital

signatures as a way of proving identity

¯

Either your

realspace identity, or É

¯

Your

cyberspace identity

¯

I.e. that

you are the online persona with a particular reputation.

¯

My legal

eagle business plan

á

For quite a

lot of people, anonymity might be a plus

¬

Lets you

opt out of the state legal system—which contracts often try to do.

¬

Protects

you in places where security of property is low

¯

Do you want

to be a programmer known to be making $50,000/year

¯

In China,

or Burma, or Indonesia, or É

¯

You might

be worried about either private seizures—kidnapping your kids, say

¯

Or public

ones.

¬

Might let

you evade taxes or regulations at home.

¯

One way of

enforcing contracts without the courts is reputation

¤

Reputational

enforcement depends on your being a repeat player, so your reputation matters

to you.

¤

It also

depends on interested third parties knowing whether you cheated someone

á

Since your

"punishment" isn't designed to punish you

á

But to keep

other people from letting you cheat them

¤

If it is

hard to know which party to a dispute is telling the truth

á

Interested

third parties will distrust both—either might be lying

á

So it isn't

in your interest, when cheated, to complain

á

So

reputational enforcement doesn't work

¤

Arbitration

is a way of lowering the information cost to third parties

á

If we went

to a respected arbitrator, or one we agreed on advance

á

And he

ruled in my favor, and you didn't go along

á

You are

probably the bad guy

¯

Another way

is structuring the contract so that it is never in either party's interest to

breach

¤

I hire you

to build a house on my property

á

If I pay

you at the beginning, it is in your interest to take the money and run, if you

can get away with it.

á

If I pay

you at the end, it is in my interest to keep the house and not pay

á

So I pay

you in installments during the construction

á

Arranged so

there is no point at which either of us gets a large benefit from breach

á

Sometimes

doing this requires costly changes in the pattern of performance

¬

Lloyd

Cohen's explanation of the consequences of no fault divorce

¯

In the

traditional marriage, women performed early, men late

¯

Many men

find younger women more attractive, so É

¯

Incentive

for a husband at forty, with the kids in school and his wife finally getting a

chance to rest

¯

To dump her

for a younger replacement

¬

How did

women change their behavior to control the problem?

¯

Postpone

childbearing in order to bring performance more nearly in sync

¯

Shift

household production to the market and get a job

¤

Which both

gets performance in sync, and

¤

Reduces the

degree to which the wife is specialized to being the wife of that man

¤

And so at

risk if he breaches.

¤

Since there

are gains from completing the contract, in a world of certainty we ought to be

able to structure payment and performance to achieve this, but É

á

In an

uncertain world, where costs and benefits may change, it's hard

á

We can

always reduce my incentive to breach by my giving you a deposit at the

beginning, which you hold and will keep if things break down

á

But that

increases my incentive to breach

¤

One

solution is to use a hostage instead of a deposit

á

I give you

something—my son, my trade secret—that

¬

it costs me

a lot to lose

¬

but

benefits you only a little to keep

¬

so pushes

down my benefit from breach a lot, yours up a little

¤

Another

solution is to structure payments so that the incentive to breach is on the

party who has reputational reasons not to

á

You are

going to do some work for me online—write a program, say

á

If you are

a repeat player with reputation, I pay in advance

á

If I am, I

pay for the program when it is delivered

á

Arguably,

these explains the feature of real contracts discussed above

¬

It is in

the interest of both parties to avoid expensive litigation

¬

The seller

is a repeat player with a reputation, the buyer is not

¬

So

substitute reputational enforcement for court enforcement

¬

Which would

you prefer

¯

To buy a

product with a long warranty from Apple or Kitchen Aid—in a world where

the warranty wasn't enforceable

¯

Or from a

no-name seller, in a world where you could sue the seller for not carrying out

the warranty?

v

Other ways

of staying out of the court

¯

So far as

possible, arrange the contract so that the result you want is the one that

happens with no court intervention

¯

Caveat

emptor is an example

v

General

observations

¯

a bunch of

simplifications

¤

cost rather

than current value

¤

Assets:

á

must be

linked to some past transaction or event

á

yield

probable future benefits

á

be obtained

or controlled by the entity

¤

assets

donÕt include good will, corporate culture, É

¤

all

probabilities are one or zero

¤

why?

¯

Compare to

tort law

¤

All

probabilities are one or zero

á

Someone

sues you for ten million dollars

á

If

probability of guilt is .4, you owe nothing

á

If .6, you

owe ten million

¤

Damages

tend to be limited to

á

pecuniary,

medical costs, lost earnings

á

less

willing to include pain and suffering and the llike

¯

in both

cases, we have to make decisions with a very crude process

¤

making

legal outcomes depend on things in complicated ways is likely to raise

litigation costs, legal uncertainty. Easier to prove a doctorÕs bill than a

pain.

¤

Accounting

aims at sufficiently clear cut decision rules

á

So that

firms canÕt easily manipulate the outcome

á

To make

them look good

á

Or reduce

their taxes.

á

At a

considerable cost in accuracy

v

Understanding

accounting

¯

First

rule—ignore Òdebit/creditÓ or reverse their meaning

¤

Most of the

time, a debit makes a firm richer

¤

A credit

poorer

¤

One

explanation: "Debit" is from Italian Debitare—what others owe

you

¤

And what

about credit?

¯

Second

rule—()= -

¯

making

sense of a balance sheet

¤

photograph

of the firm at an instant—compare two dates

¤

show a list

of assets, most liquid at the top, at two periods

á

group into

current assets, total

á

and long

term ("property, plant and equipment") and total

á

total the

two totals for total assets

¤

similar

list of liability and owner's equity

á

liability a

negative asset

¬

probable

sacrifice of economic benefit É

á

why do you

put equity with liabilities?

á

How much

wealth does the firm itself (as opposed to stockholders and others) have?

á

the

fundamental equation

¯

making

sense of an income statement

¤

designed to

show the changes over a period of time

¤

money coming

in: Sales revenue (or equivalent for other sorts of firms)

¤

costs

á

cost of

goods sold—raw material, labor, etc.

á

operating

expenses: Costs not attributable to particular output

á

interest

expense

á

income tax

expense

¤

at each

stage, you have a net to that point

¤

and end up

with net income

¯

making

sense of a cash flow statement

¤

the one in

the book

á

money comes

in as net income, but É

á

if part of

the "income" is accrued but not received É

¬

it goes

into accounts receivable, not cash,

¬

so less

cash

¬

reverse if

some accounts from last year are paid, increasing cash

¬

so subtract

from income the increase in accounts receivable

á

accounts

payable the same thing in the other direction

¬

we

subtracted out expenses in calculating income, but É

¬

if some

expenses were accrued but not paid É

¬

we still

have the cash

á

we

subtracted out depreciation in calculating net income—but they didn't use

up any cash. Add back in.

á

also cash

flows from

¬

borrowing

(increases cash)

¬

paying

dividends (uses up cash)

¬

etc.

¯

making

sense of T-accounts

¤

The T-account

records a single transaction, not a balance or a total over time

¤

each

transaction is entered twice

¤

if you buy

something

á

that

decreases cash, increases asset (land, factory, raw materials)

á

if you sell

something, increases cash, decreases inventory

¤

what if you

make money?

á

Buy

something for $100

á

Sell it for

$200

á

How do you

make the accounts balance?

¯

Joyce James

Case

Joyce

James graduated from college in June 2002. As was traditional in the James family, JoyceÕs parents paid all of her

expenses through college. But,

upon graduation, she was expected

to fend for herself financially.

On the date of her graduation, Joyce had neither financial

resources nor financial

obligations. Now that she is

responsible for her own finances, one of her friends has suggested that she might want to think

about putting together a financial statement of some sort. What sort of financial statement do you

think would be useful for Joyce?

How would you propose

she account for the

following transactions?

1.

At her graduation exercises, Joyce was awarded a prize of $5,000 her senior

thesis on Day Hiking in Ireland.

The prize came in the form of five one thousand dollar bills.

2.

She spent $2,000 of the prize money buying books she would need for graduate

school,

which

she was planning to attend in September.

3.

She spent another $2,000 traveling through Europe over the summer and

collecting memories of a lifetime.

4.

At the end of the summer, she took out a $4,000 loan to cover the costs of

graduate school.

v

Why might she

want to work out a financial statement?

¯

To keep track of

her situation—decide if she is too much in debt, etc.

¯

For other

people—to get a loan, É

v

What kind of

information is most useful to her?

¯

Probably a

balance sheet, showing her assets and liabilities

¯

But to get there

we will use T-accounts—more for our information than hers.

v

How do we record

the prize?

¯

She gets $5000 in

cash—where does that go?

¯

What's the

balancing item?

¯

Is there a

reduction in some other asset?

¯

An increase in a

liability?

¯

If not, what's

left.

v

She spends

$2000 on books for grad School

¯

Where does

the expenditure go?

¯

What's the

balancing item?

v

She spends

$2000 traveling in Europe and collecting memories?

¯

Where does

the expenditure go?

¯

Are the

memories an asset?

¯

If not,

what balances the expenditure?

v

She takes

out a $4000 loan to cover the costs of graduate School

¯

Where does

the loan go?

¯

What

balances it?

v

She spends

$5000 on living expenses in graduate school

¯

Where does

the expenditure go?

¯

What

balances it?

v

Now put

this all together for a balance sheet

¯

What are

her assets?

¯

What are

her liabilities?

¯

What is her

equity?

v

Is this an

accurate account of her actual situation?

¯

For what

purpose?

¯

Are you

thinking about loaning her money?

¯

Or marrying

her?

v

The

matching principle

¯

So far as

possible, we want to put revenue and the associated costs in the same period

¯

So that we