A Folding

Armchair

Some years back, Master Hal Raeburn made me a folding chair with arms.

It is a very comfortable design whose only fault is that it does not

fold very

flat and so is a bit of a nuisance to transport--at least when my wagon

is

packed and overflowing for Pennsic. The design goes back to at least

the

14th century; the 16th century version is

sometimes called

a "Dantesca" chair. This year I decided to make a scaled down version

for my

son. Since I am not as good a woodworker as Hal, I simplified the

design

somewhat. I also modified it in order to make it possible to take the

chair

apart.

General Considerations

I used oak, which is a strong wood and readily available; if you use

something weaker, such as pine, you may want to alter the design to use

thicker

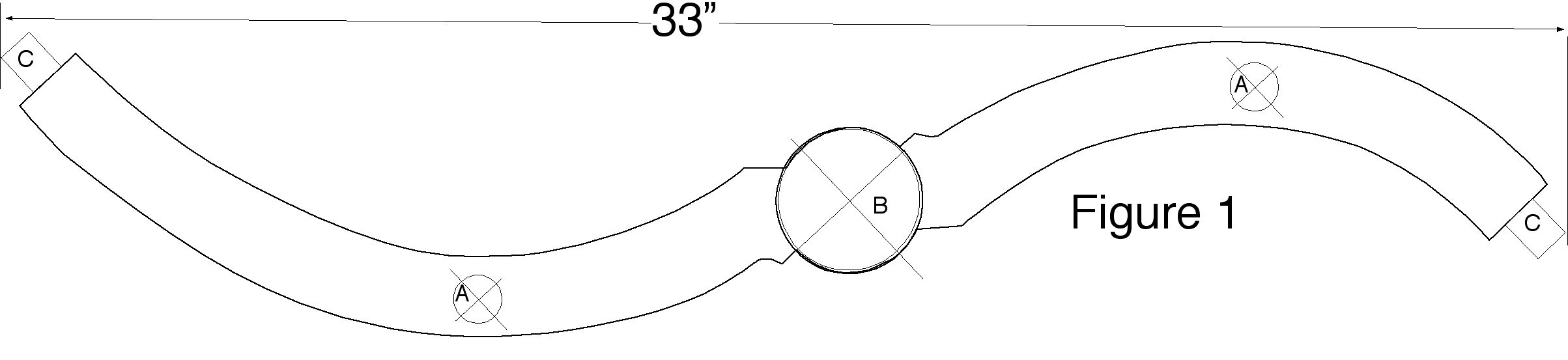

pieces. The figures show the pieces at 100%--scaled for the chair I

use, not the

90% version I made my son. I am 5' 3 1/2" and my chair was made

specifically for

me; if you are substantially taller or shorter you may want to scale

the design

accordingly. The easiest way of making patterns is to copy the figures

from

this webbed article into a drawing program, scale as desired and print.

For

cutting curved pieces I used a band saw. If you don't have access to

one, use an

electric jig saw. If you don't have that, a hand jig saw should do it,

although

I expect it will take longer.

For blind

mortresses--the sockets in the chair arms and feet--I first drilled a

hole of

the appropriate size then used chisels to square it. For grooves I used

a table

saw; if you don't have access to one a hand saw, or a chisel, should

work.

Making the Chair

On the left is the chair Hal made for me, on the right the chair I made

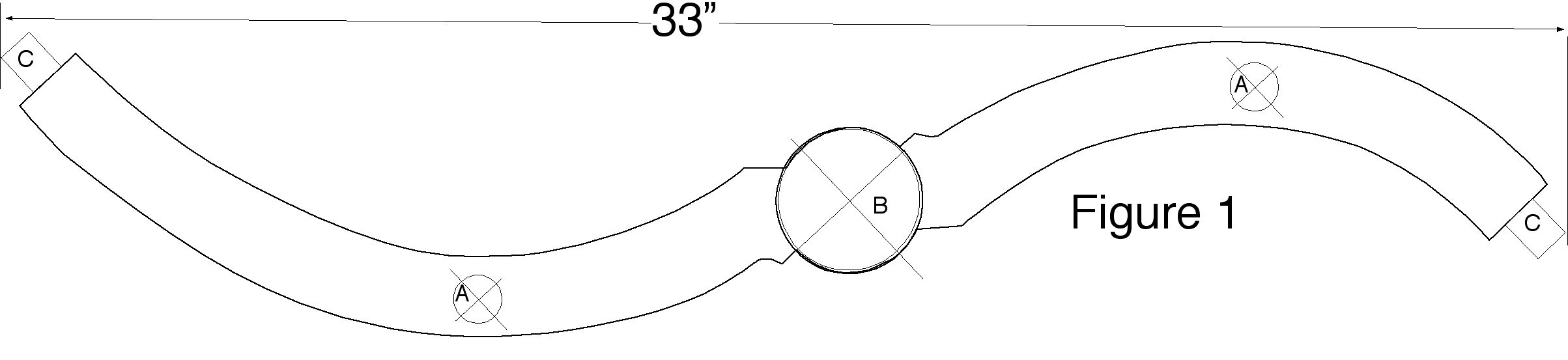

for my son. Figure 1 is a cutting pattern for one of the four S shaped

pieces

that make up the main structure. The pieces are identical except for

the holes

(A) drilled part way through them for the horizontal dowels to fit

into--on two

pieces they are on one side of the board, on two the other side.

The tricky

part of these shaped pieces is that the circle (B) in the center of

each is only

half the thickness of the board, in order that two can fit together as

shown on

the next page (bottom right).

I found that the easiest way to make them was to first cut out the

piece,

then use an adjustable drill bit, set for the radius of B. The bit cuts

a

circular groove and also removes the wood inside the circle, although

not to the

full depth of the groove. Additional wood can be removed with a chisel.

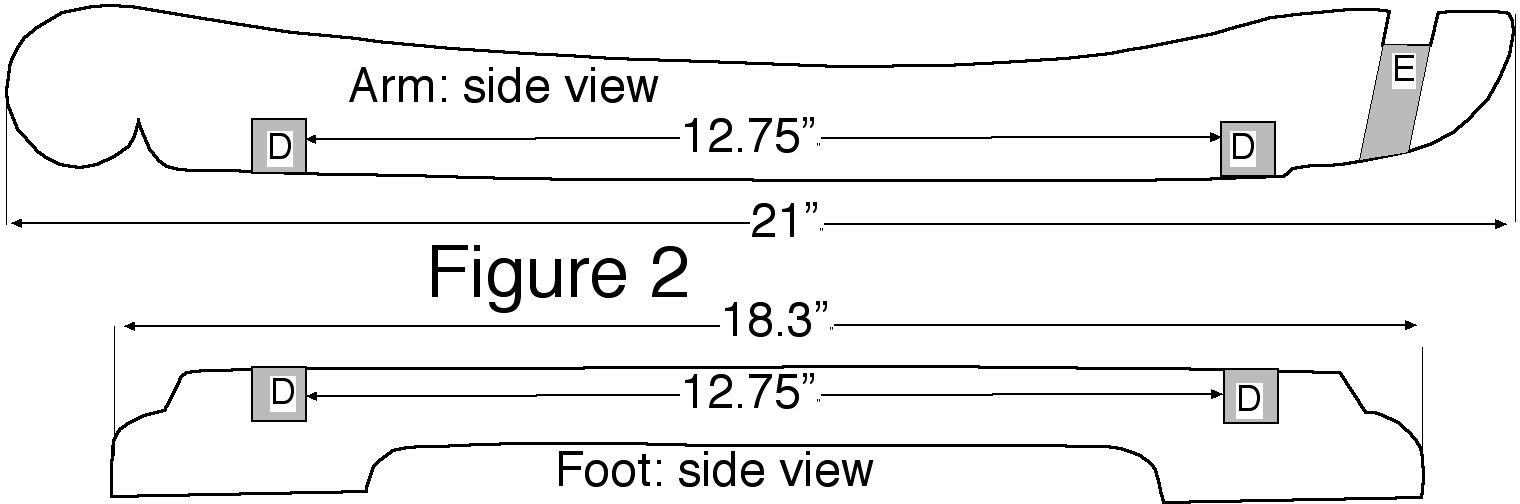

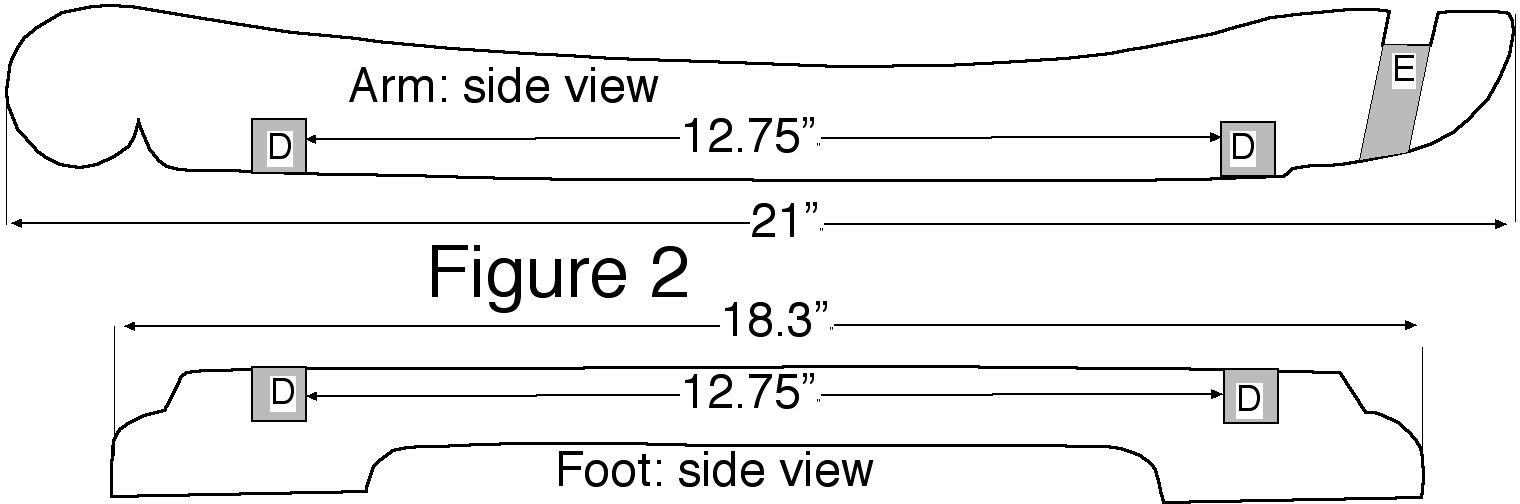

Figure

2 shows the arms and feet; thickness, the dimension not shown, is 2".

The shaded

squares (D) are blind mortresses--sockets that the tabs (C) on the end

of the S

pieces fit into. The shaded region E is a groove that the back slides

into. Its

exact width sshould be the same as the thickness of the back, either

1/2" or

3/4" depending on your relative preference for lightness or strength.

For

the chair I made my son, which was scaled to 90% of the full sized

chair whose

measurements are shown, I used 3/4" oak for the S shaped pieces. The

original

was 1" hardwood--which might be better for a full sized chair intended

to be

used by a reasonably heavy adult. You will also need four dowels. Their

length

should be the distance between the near sides of the sockets in arms

and legs,

since that is the separation of your two pairs of S pieces, plus twice

the depth

of hole A, into which they fit--from the separation of the sockets in

Figure 2,

that comes to 12 3/4"+3/4"=13 1/2", assuming the holes are 3/8" deep.

Diameter

should be the same as hole A--about 1" for the full sized version of

the chair.

Once you have cut all the pieces and made sure that the pairs of S

shaped

pieces fit together and that tabs C fit into sockets D, the next step

is to

drill a hole at the center of

each

circle B. To make the two pivot pieces that go through those holes, cut

two 2

3/4" lengths of 7/8" hardwood dowel and two circles of 3/4" hardwood

the same

size as circle B. Drill a 7/8" hole part way through the center of each

circle

and glue the dowel into it, giving the mushroom shaped piece shown to

the

left.

Assemble two S pieces and one pivot piece as shown below. Repeat for

the other pair of S pieces. Make sure to assemble the legs so that all

the holes

A, drilled part way through, face inwards and both pivot pieces face

outwards.

Assemble the whole thing, with tabs in slots and dowels in holes A.

To

keep the pivot from coming out, drill a hole through the pivot dowel on

the

inside side of the S pieces and put a small dowel through it, as shown

above.

The picture below shows how it now looks--a chair minus back and seat.

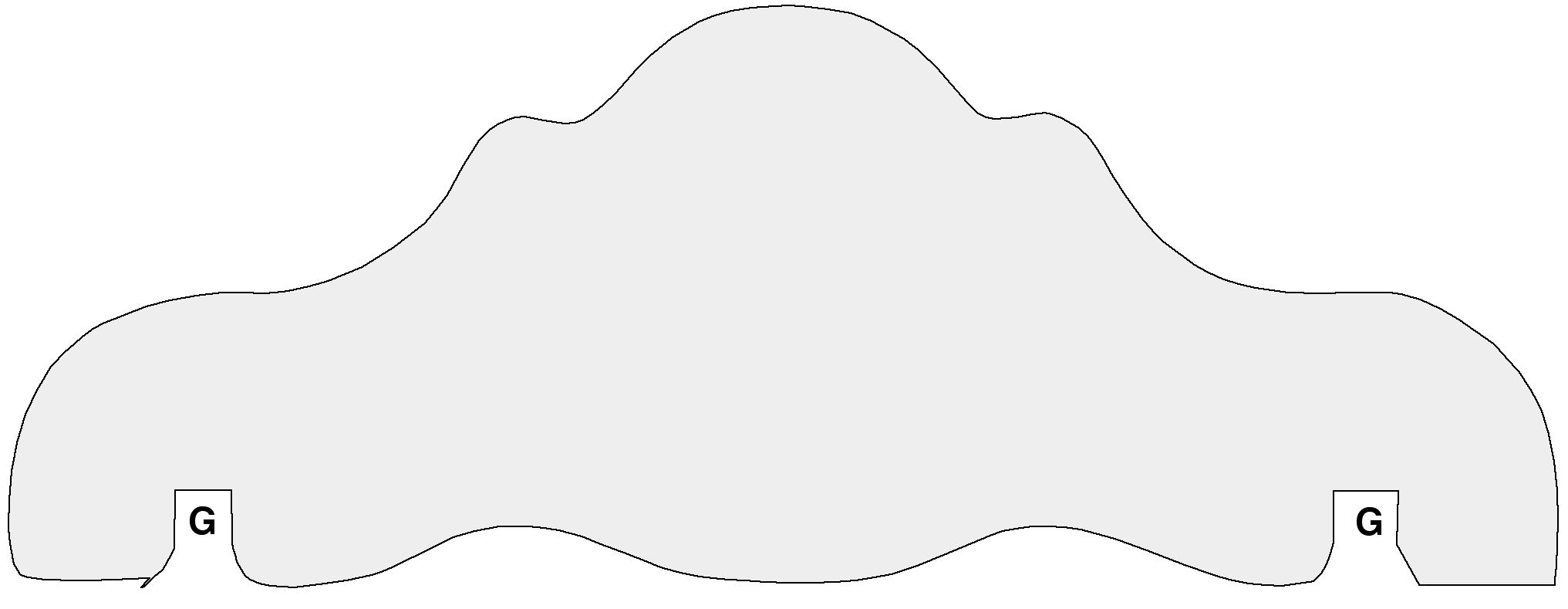

Figure

3

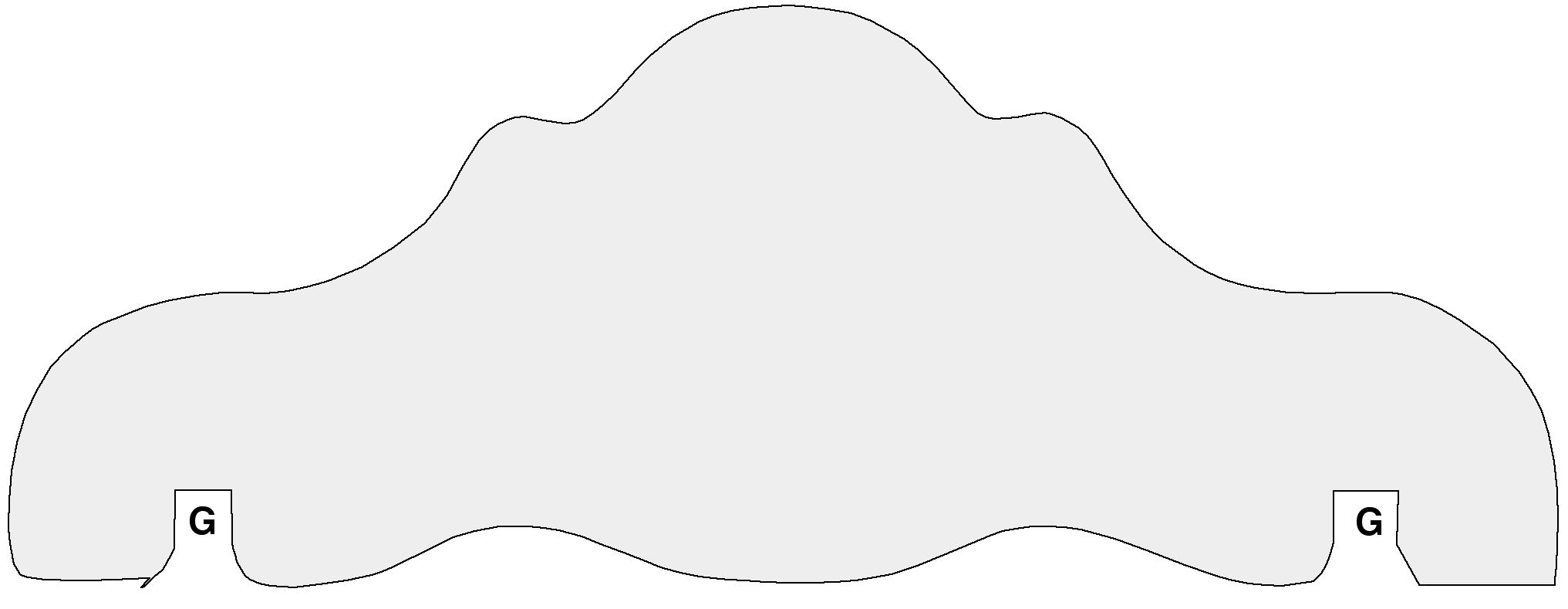

Figure

3 is an approximate cutting diagram for the back--its aesthetic

excellence

should be credited to Hal, whose design I copied. Use either 1/2" or

3/4" wood.

Scale, or otherwise modify, the figure so the slots (G) are the right

distance

apart, and the right width, to fit into the grooves in the arms. This

is best

done after you have the rest of the chair assembled, since the exact

separation

of the arms depends on the exact angle at which the S shaped pieces

cross, which

in turn depends on fine details of the

pieces.

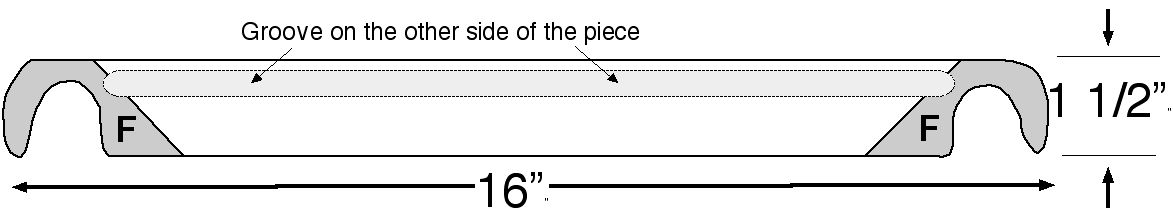

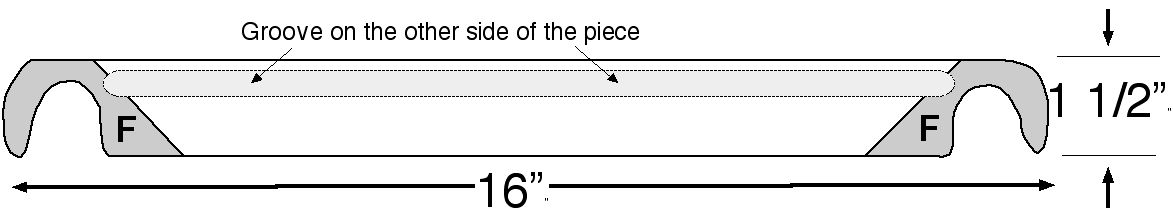

Figure 4

Seat

The seat consists of two support pieces of oak about 2"x1 3/4"x 16

1/4" and

one piece about 12 3/4" x 12 1/2" x 1/2" that makes the seat itself;

figure 4

shows a side view of one of the supports. The 1/2" piece goes into

grooves cut

into the inside surface of the supports--the surface away from the

adjacent S

piece. Exact dimensions should be calculated, like the exact form of

the back,

after the rest of the chair is done and you can measure the separation

of the

two upper dowels. The pictures below show a top and bottom view of the

assembled seat.

For my chair, I made the grooves 3/8" wide and 1/2" deep, then

planed half

an inch on each side of the seat down to 3/8" to fit, but if that is

too much

trouble you could use 1/2" wide grooves instead. The outside surface of

the

thick pieces is inset at the end--shaded area F--so that the edge of

the

assembled seat can fit partly over the adjacent S piece, as shown

below.

Disassembly

The chair, minus back and seat, consists of two closed loops of

wood--front S piece to foot to back S piece to arm to front S piece

again. In

Hal's version, one of the S pairs crosses right over left, the other

left over

right, with the result that one of the two loops is just inside the

other. This

prevents the loops from moving forward or back with regard to each

other,

supplementing the effect of the cross pins on the pivot pieces. It also

means

that the two loops can, in principle, be separated without taking

either apart.

In practice, however, the chair is sufficiently rigid so that it would

be

difficult to separate the crossing pieces far enough to make that

possible.

One way to make the chair more transportable is to never glue on the

arms,

legs, and dowels, relying instead on the tabs being tight enough in the

sockets

to hold the piece together. That is what I did on the 90% version I

made for my

son; since I am writing this after making it but before using it at

Pennsic, I

don't yet know whether there will be any problem with spontaneous

disassembly.

If so, I have glue in my toolbox.

For an earlier and smaller version of the

chair I used a different system. The paired S pieces cross the same

way, which

means that the two loops are interlocked but, once the pivots are

removed, not

held together. I left one foot and the corresponding pair of dowels

unglued;

removing them lets me separate the two loops, which nest together much

better

separately than together.

Final Comments

Once everything is made, sand or file round any sharp edges or corners

that you don't want sharp, assemble it, glue on feet, arms, and dowels

(or not,

depending on whether you want to be able to disassemble it later). I

finish my

furniture by wiping on boiled linseed oil, leaving it fifteen minutes

or so,

wiping it off, and repeating four or more hours later, then letting the

whole

thing dry for a few days. The result on oak looks beautiful and

provides some

protection, although perhaps less than with more modern finishes.

Linseed oil is

a period material; I have been told that it was used for finishing

furniture in

period but have not actually seen the evidence. I have also been told

that a

linseed oil finish works better if you use oil heated to 135° F,

but have

not yet tried doing it that

way.

Cariadoc

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Medieval.html