Thomas Howe

Legal Systems Very Different From Our Own

Prof. David

Friedman

May 18, 2006

Introduction

The Ottoman Empire’s birth

is properly dated in 1453, the year the Ottomans took Constantinople (the

conquest). Prior to this, the Ottomans were a principality surviving in the

fluctuating border regions of more powerful Islamic states and the Byzantines.

The term “Ottoman” does not describe an ethnic or racial group.

Instead it most properly applies to the final version of the evolving governing

class of the Oguz Turks, a nomadic people whose origins are in Central Asia. As

this branch of the Turkish family fled from Mongol pressure in Central Asia to

the Caucuses and Asia Minor, it adopted Islam and learned statecraft from the

predecessor Islamic groups and Byzantium, the leading bureaucratic state of the

West.

Originally, the

Oguz Turks had two classes, the warriors and the subjects. The subjects were

peasants. The vast majority of these were Muslims, Christians or Jews. But as

the Ottomans successfully expanded their territory under the same crusading

expansionist spirit the characterized Islam’s early history, the ruling

class lost its ethnic identity. Though, critically, it strictly maintained its

cultural characteristics. The true Ottoman ruling class was defined by

essential cultural commonalities. These commonalities were Islam, mastery of

the Arabic, Persian and Turkish languages and literatures, extensive education

either at home, the

medrese schools or

in the Palace school in Istanbul and career membership in the massive

bureaucratic/military structure set up to rule, expand and maintain the empire.

Ethnic origin mattered little, and many Sultans were the sons of female slaves

from conquered or client lands.

[1] After the conquest of

Constantinople, the more successful Ottoman Sultans were seen as consolidators

of the central power through expanding and refining the bureaucracy. This was

done for several reasons. First, it allowed the Sultan more control over

ethnically, religiously and geographically diverse lands and peoples by

expanding the government’s ability to keep records and thus tax these

groups. Second, an active and expansionist government gave the ruling class the

ability to react to the diverse influences that were constantly influencing

Ottoman society. These influences included the Turks Asiatic Steppe origins,

the different legalist school and threads of Islam (the Ottomans largely

followed the Hanafi school),

[2] the neo-Platonic

philosophies of conquered Greeks, the high artistic culture and literature of

Persia, the rise of Western Europe and the need to maintain cultural identity

while also being a nexus of world trade. The Ottomans formed their empire in a

rich and fluid part of the world and they had contact with nearly all the major

cultures of the old world.

During the consolidation phases

that followed the establishment of Empire, the ruling class split into three

distinct parts: the military administrators, the judiciary, and the bureaucratic

civil administration.

[3] These three groups were

nominally independent in terms of recruitment, education and career tracks, but

since they were all under the sultan, moves between branches were made as

needed.

[4] The defining characteristic of the

Ottomans was not their people or unique culture, but their government. The

Ottoman government was set up to run a massive empire made up a multitude of

peoples whose cultures sharply contrasted. To adapt to this, the Ottomans set

up a poly-legal system in which a person’s religion and gender determined

what legal rights and obligations they had, both to their fellow subjects and to

the state. The Ottomans greatest innovations came not in invention, but in

incorporation of the strengths they were exposed to while balancing their own

cultural norms and those of their subjects. Ottoman greatness was embodied in

their ability to balance innovation and the status quo – largely through

their legal system, which tolerated and encouraged very high levels of

self-government.

The telodic function of the

Ottoman government was to wage holy war against infidels, maintain a domestic

status quo and collect taxes. The Ottomans felt that these purposes reflected

what they called ‘the circle of equity.’ The circle is a political

concept that states,

1.) There

can be no royal authority without the military.

2.) There

can be no military without taxes.

3.) Taxes

are generated by the under classes.

4.) The

sultan keeps the under classes by ensuring justice.

5.) Justice

requires harmony in society.

6.) Harmonious

society is a garden, its walls are the state.

7.) The

state is sustained by religion.

8.) Religion

is supported by royal authority.

[5] These statements were usually

written around the circumference of a circle, showing how the eighth statement

led directly back to the first.

[6] The basis of

this political reasoning rested on the division of society into the ruling

Ottoman class and the subject under classes. The Ottomans sought to maintain

this relationship by working out agreements with their subjects which would

result in the under classes largely ruling themselves. To this end, the

Ottomans dealt with both geographic and cultural diversity within their empire

by expecting their subjects to self regulate. One Ottoman technique was

empowering and encouraging their subjects to convert to Islam and thus join the

community of Muslims (

umma) or to

accept certain conditions in exchange for recognition and protection by the

state.

[7] The Ottoman

bureaucracy, following the models of earlier Islamic states, expected the

subject non-Muslim communities to deal with their own internal affairs and

deliver on their tax obligations. These groups were called

millets and had powers of taxation and

collective representation before the Ottoman

state.

[8] Very often the groups were allowed to

choose their leaders and were largely divided up by civic units for tax and

judicial purposes.

[9] In order for a group to be

granted

millet status, it had to

convince the bureaucracy of certain threshold issues. First, the group had to

establish itself as a cohesive religious community rooted in

history.

[10] Innovation was frowned upon.

Second, it had to nominate leadership that would be responsible for taxes and

communication to the Ottomans. Third, the group had to accept the Pact of

Umar.

The Pact of

Umar is a series of promises and obligations between Islamic states and their

non-Muslim citizens and reflects the evolution of Islam and its relation to its

sister monotheistic religions. To fully understand this document, a basic

understanding of the history of the expansion of Islam is needed.

Mohammed’s Arabs were conquerors. Between 632 C.E. and 750 C.E. the

Muslims reached the borders of France and

China.

[11] This put them in political control

of millions of non-Muslims. Since the Koran taught tolerance for fellow

monotheistic religions (Jews and Christians, or “People of the

Book”), but vacillated on just how that tolerance was to manifest, early

Arab conquers combined both the teaches of Islam with the realities that they

found themselves in. Historically, most non-Muslim groups in Muslim lands

became marginalized as peoples inevitably converted to Islam for social and

economic reasons.

[12] This

marginalization of minorities was balanced by the tolerance taught by the Koran

and eventually distilled into the Pact of

Umar.

[13] Muslim tradition states that the

Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (634-44) issued the pact to the Christians of

Jerusalem, or alternatively Syria as a whole, following its fall to the Muslim

armies.

[14] Although Western scholars have

ascribed the formulation to the Umayyad caliph, Umar II (717-20), it may be that

the its final formulation is a composite of many different agreements between

Muslims and non-Muslims.

[15] In its earliest

and most basic formulations, the pact stipulated that in return for the

Muslims’ pledges of safe-conduct for their persons and property and of

non-interference in any internal autonomy the non-Muslims would agree to the

following:

1.) They

would be subject to the political authority of Islam.

2.) They

would not speak of the Prophet Muhammad, his Book, or his faith.

3.) They

would refrain from committing fornication with Muslim women.

a. This

was extended to include marriage between non-Muslim men and Muslim women.

b. Marriage

between Muslim men and non-Muslim women was allowed, following the

Prophet’s example, as long as the children were brought up as Muslims.

c. But

non-Muslim wives of Muslim men were free to worship according to their own

faith.

4.) Non-Muslims

were forbidden to sell or give a Muslim anything that was in violation of

Islamic law, i.e. carrion, pork, or alcohol.

5.) The

display of crosses or ringing of bells in public was not permitted, nor any

public proclamation of “polytheistic” belief to a Muslim. This

included references to the Trinity.

6.) No

new churches or synagogues could be built.

7.) Non-Muslims

must wear the girdle over their cloaks and were to differentiate themselves from

Muslims by their headgear, mounts, and saddles.

a. This

was expanded later to prohibit non-Muslims from riding either horses or camels,

limiting them to mules and donkeys.

b. Often

local variations took root. In Aleppo non-Muslims were to wear red shoes. In

other cities, there were to wear only blue or black clothing.

c. Everywhere,

non-Muslims were to refrain for using green, the prophet’s color.

8.) No

non-Muslims could hold a Muslim as a slave.

9.) No

public religious processions, such as those traditionally held at Easter, were

to be allowed.

10.) Non-Muslim

communities agree to pay the

jizya, or

head tax on every non-Muslim male in Muslim

lands.

[16]The pact stipulated that if a

group faithfully followed its strictures, the state would largely not interfere

in their internal administration. As such, decisions made by the leadership of

the non-Muslim religious communities in regards to personal status law or

contracts unless all parties agreed to Muslim

adjudication.

[17] While the pact allows

non-Muslims to retain their own customary practices in regards to personal

status law, it established a public disdain for those practices in the eyes of

the Muslim legal scholars and kadis and, by extension, the

state.

[18] Critically, “it established

the primacy of the Muslim population over the non-Muslims in any public space

the communities might share. The call to prayer might disturb a

non-Muslim’s slumber, but the ringing of the church bells or the chants of

the non-believers should not inconvenience a

Muslim.”

[19] Additionally, Non-Muslims

had to pay the

jizya, but the amount

assessed in the Ottoman period was usually more symbolic than onerous because

the tax was calculated on the man’s ability to

pay.

[20] Under the pact the Ottoman’s

allowed

millets to establish and

maintain their own, internal legal structures. This respect for minority group

autonomy was so great that kadis and local officials would routinely enforce the

orders of

millet courts.

Only when all

parties agreed or when one of the parties was Muslim, would legal issues be

heard before a kadi. Non-Muslims had difficulty achieving justice there,

however, because of the high evidentiary burden sharia places on those making

claims against Muslims. In 18

th

Century Aleppo, a Christian chronicler described the murder of a Christian

merchant.

[21] A Muslim contract worker

approached the merchant and asked for work.

[22]

The Christian merchant said that he had none to offer and the Muslim contractor

pulled his dagger and killed the merchant.

[23]

Since there were only Christian witnesses, no charges against the murderer were

brought.

[24] This violated the standard

evidentiary burden outlined in sharia that required two adult male Muslims as

witness against a Muslim on a murder charge.

Minority groups

would use the Ottoman court system to enforce their own internal decisions.

Records abound of the Patriarchs of Constantinople condemning corrupt or heretic

priests.

[25] Local kadis or the central

government, satisfied that the dissidents were properly tried under the rules of

their group, would then enforce the groups

ruling.

[26] Enforcement by the Ottomans of

religious minority decisions ran the gamut of removal from office to executing

those condemned by their own groups.

[27]Some groups

prevented their members from using the Ottoman court system. A resident English

consulate in Aleppo claimed that the rabbis of his city “had issued

injunctions forbidding any of their community from bearing testimony against

another Jew in the Muslim courts.”

[28]

This does, however, contrast with the Jewish population of Jerusalem and

Damascus, which used the Muslim courts often to resolve their internal

conflicts.

[29]

Ottoman Sources of Law – Sharia and Kanun

The Ottomans, being good

Muslims, took the sharia as the basis of their jurisprudence. The Ottomans,

being good Turks, also relied heavily on their ancestral practices, which

sustained them before Islam and helped them to gain their empire. Being good

administrators as well, the Ottomans adopted, merged, or even sometimes ignored

these precedents over the course of their empire.

At its origins, Sharia

gives rules for running a community of like believers. The Ottomans, however,

ruled a massive empire of diverse communities, thus they built upon and adapted

the religious law. Ottoman secular law was steeped in their nomadic Turkish

origins. When Mehmed II was consolidating the empire after his conquest of

Constantinople, he issued a

Kanunname.

This ‘dynastic law’ was a codification of customary practice with

commentary and instructions for his successor on how to rule in the

“Ottoman Way.”

[30] “That

portion of the Conqueror’s institutes dealing with the structure of the

central government ... which formed the effective constitution of the Empire,

was thus a mixture of description of actual practice, acknowledgment of

precedent, and prescription emanating from the ruler’s discretionary

authority, all given canonical

force.”

[31] “Kanum was an

accretive and, within limits, mutable phenomenon. The institutes of the

‘founding father’ were to be binding on his descendants, for they

expressed the dynastic mandate. But Mehmed also enjoined his successors to

amend usage as necessary. Kanun was not to be changed willfully, however, but

only in accordance with the spirit of impersonal justice and dynastic honor that

informed the primal promulgation.”

[32]

Kanun not only regulated the structure

of the Ottoman government, but also “dealt with general matters of

provincial military organization, penal justice, taxation, and the position of

certain minorities within the

Empire.”

[33] The Ottomans did not use the

laws of their conquered subjects for their own internal purposes (aside from

adopting many Byzantine and Persian governing practices), however, they did

carry out the court decisions of the

millets and allowed minorities access

to both substantive Ottoman law and court procedures when appealing

millet decisions.

While

Christians and Jews “appeared frequently in the Muslim courts in the

Arabic-speaking provinces and apparently showed no hesitancy to press cases

involving breach of contract against Muslims, the recorders of their testimonies

have left semiotic evidence it was not on the basis of

equality.”

[34] Individual Christians and

Jews were always identified by their religion when entered into the records, an

indication that the court scribes considered “Muslim” to be the norm

and unnecessary for notation.

[35] Non-Muslim

men were further set apart from Muslims by the scribes in both Aleppo and

Damascus who recorded their patronymic as “walad,” for example,

Jirjis walad Tuma (George son of Thomas), as opposed to the “ibn”

reserved for Muslims.

[36] This makes sense in

light of the hierarchies that exist in Islam, between men and women, believers

and non-believers, saints and sinners.

The testimony of a non-Muslim

was accepted in court with the swearing of the appropriate oath, on either the

Torah or the Gospels. Despite the Koranic injunction that the testimony of two

non-Muslim males, or two Muslim women for that matter, was required to equal

that of one Muslim male, non-Muslims and women testified against Muslim males on

an equal basis.

[37] There was a difference,

however, between the two classes of witnesses. Women of whatever faith were

generally required to present two male witnesses as to their identity, while

non-Muslim males were accepted on their own

assurances.

[38] The physical descriptions of

non-Muslim males were sometimes recorded as an apparent identity check, however,

as was often the case for slaves.

[39] Such

physical descriptions were rarely, if ever, added in the case of free Muslim

males.

[40] Despite such hints of possible

discrimination, “at least in the eyes of the recording secretary,

non-Muslim men and women were frequent visitors to the Muslim

courts.”

[41] But, “as non-Muslims

often relied on Muslim witnesses to win their civil cases against Muslims, we

can assume that they understood the efficacy of having Muslim testimony to sway

a Muslim judge to their side.”

[42]

The Ottoman poly-legal system

was a balance of criminal and torts actions. The Ottomans carried out the

sharia. They also allowed the millits

to carry out their own law. If there was a choice of law, the choice would

inevitably be to follow Ottoman law. In the Ottoman system, claims were heard

before a kadi, who applied the Ottoman understanding of their own and the

minority laws.

Appeals System

The Ottoman

ideal was true justice via correct application of the

law.

[56] Speed was always helpful, but often

just an ideal. If matters were appealed to Istanbul (either through a limited

system of rights to appeal or through direct intersession by the central

government), the bureaucracy would hear issues on Ottoman law or

sharia anew, but issues of millet

(Jewish, Christian or other law) or foreign law (French, Venetian or other law),

would only be reviewed for factual error or jurisdictional

error.

[57] This tenet was largely based on the

pact of Umar, which guaranteed minority groups the right to run their internal

affairs. Foreigners received protection largely based on the Ottoman’s

treaty obligations to their home states.

[58]

Additionally, all subjects of

the Sultan, whether Muslim or not enjoyed a right of appeal directly to the

central government.

[59] This was an ancient

Islamic practice, traced back the first four caliphs who “extended justice

to non-Muslim petitioners, even at the expense of their trusted

lieutenants.”

[60] While most courts had specific

jurisdictions (often geographic, military, market, or community or

millet based), Ottoman subjects did

have some choice of courts.

[61] Non-Muslims

could have cases heard in Ottoman courts and in the larger cities, groups could

go to specialized Islamic courts that practiced the different schools of

sharia interpretation. These could all

be appealed, but usually only on the claim that the chosen form of law was

incorrectly applied.

[62] Unusually, an appeal

might be won on the basis that the chosen school or form of law did not actually

apply to one group or another.

[63]

Guild Regulations

Muslims and non-Muslims worked

together in many of the trade guilds and went as a collective unit to voice

guild concerns before the court, although the names of Muslims were always

listed first in such depositions.

[64] If the

guild had partial Muslim membership, the head of the guild was invariably a

Muslim, though his second in command would reflect the majority

population.

[65] Not all the guilds were

religiously integrated.

[66] But guilds

consisting mostly of Muslims were usually low prestige jobs such as tanners or

porters, the membership of which was typically of tribal origin.

Marriage Law

While marriage

was one method of expression of adulthood for men, marriage was almost the

exclusive route for women. Ottoman girls were married off between their

12

th and

14

th years and, when widowed, were

encouraged to marry again quickly.

[67] New

brides entered the orbit of their husband’s families. Indeed women were

so defined by their new families that most post-pubescent education and domestic

instruction was managed by a woman’s

mother-in-law.

[68] The Ottomans

used an arranged marriage system. This process started when a family decided

that it had a single male who was ready to married. Men were given a great deal

of leeway regarding when to marry but where expected to marry by 30; allowing

for time in military service, advanced education or other career development.

His family would thus start scouting for marriageable girls. His family would

do this by either employing a female member close to the man, usually his mother

or a close female relative or a professional matchmaker as scout for

marriageable girls and women.

[69] The scout,

called a viewer

(

görücü), usually had an

eye out for marriageable girls ahead of time, and if an especially promising one

was found, a man’s family might pressure him to start thinking about

marriage before she was snatched up by another family. A

görücü would likely

choose from among the girls she saw at the public

baths.

[70] If the

görücü was a

professional matchmaker, she likely traded on her access to lots of young

women.

[71] The source of this access was

likely the

görücü’s primary

business engagement as a

kira

(merchantwoman).

[72] Because women

sequestered away in harems were not allowed to leave and were often prevented

from even shopping in the bazaars by jealous husbands, merchant women would come

to them to sell jewelry, bolts of cloth and other domestic

goods.

[73] Since these merchantwomen had

access to the harems within their spheres of operation, they were one of the few

people to have a good idea about the looks, qualities and availability of the

women of their districts.

[74] After

identifying potential candidates, that

görücü would arrange for

a viewing.

[75] These viewings were very

ritualized and followed a prescribed format. The

görücü would sit with

the girl’s mother or female guardian and exchange pleasantries and also

any articulated requests by the prospective groom in what he wanted in a

bride.

[76] Then the candidate(s) would

“come into the room dressed in her best, salute the guest with

handkerchief and, with downcast eyes, hand out dainty coffee cups

(

fincans) set in silver containers

(

zarfs).

[77]

“[The

görücü]

would drink the coffee slowly in order to have time for inspection – for

when the coffee was consumed the girl withdrew – and also to keep from

hurting the girl’s feelings by a too hasty

dismissal.

[78] Then as soon as the girl left

the room, the elders would get down to

business.

[79] Details discussed would include

what the

görücü thought

of the girl, the mother describing the “girl’s trousseau, including

jewelry.”

[80] The looked over girl would

later consult with her nurses and sisters and immediately report if the

görücü “handed

back their coffee cups too soon or

not.”

[81] After viewing

candidates the

görücü

would head back to the man’s family to discuss with him and his guardians

the supposed compatibility of the pair and the advantages to both families

stemming from the union.

[82] The girl had two

things to offer: her beauty and her family connections “and a girl’s

plainness could be compensated for by her family’s

influence.”

[83] After the reports of the

girls had been given to the man and his parents, the advantages of the potential

arrangements were discussed in a family

council.

[84] At these councils the man’s

female relations were expected to do most of the talking and were also expected

to come to a consensus, the male relatives, speaking through the man’s

father, were expected to agree.

[85] Before

proceeding further, the girl’s father needed to give approval. Usually,

the two families were known to each other and viewings would likely not have

taken place if the women involved thought the match improper in some way. If

the girl’s family did not know much about the man’s, it was expected

and understood that the man’s father would do an extensive check into his

family’s finances and his career and economic

potential.

[86] Additionally, the girl’s

family could pull out at any time prior to the marriage ceremony by resorting to

the study of dreams or

istihare with

the ambiguous but authoritative pronouncement that, “Our dreams did not

turn out well.”

[87] If the

girl’s family felt that the groom’s family was of the right

character and resources, then a series of family visits

ensued.

[88] Representatives of the two

families would then meet to settle the trousseau and dowry and to set dates the

dates of the formal engagement and the legal ceremony to bind the two in

marriage.

[89] These were considered social

issues and were thus often settled by the matriarchs of the families. To the

extant that this was an economic decision, it was a decision based on what would

be a fixed amount of worth, one that the men could comment on ahead of

time.

[90] The husband’s father would

then call on the bride’s father for a final promise of his daughter

“at the command of God and the

Prophet.”

[91] The men would then decide

in whose household the new couple would

live.

[92] At its base this was an economic

decision that had far reaching ramifications, not just in terms of the earning

power of the husband but in terms of the domestic contributions of the wife to

the greater family community.

[93] Additionally

due account was likely taken of the potential impacts such a move would have on

the husbands career prospects, a critical issue for Ottoman men.

[94]Once these

agreements were worked out and sworn before God, the husband’s family

would start on the delivery of the dowry.

[95]

The Ottomans practiced dowry by dividing it into two

parts.

[96] The first, and smaller portion, was

paid before the marriage contract was

signed.

[97] Its purpose was to help defray the

cost of the wedding and to contribute to the furnishing of the young

couple’s home.

[98] The greater portion

of the dower was the sum the husband contracted to pay his wife in the event

that he divorced her.

[99] This sum also came

to her if he died while she was still his

wife.

[100] In this way, the bride’s

family was assured that she would be taken care of by either her husband or the

rump of her dower.

Once the small

dower payment was made to defray the costs of the wedding, the husbands mother

and female relations would visit the bride and her female relations bearing red

silk and candy.

[101] The red silk would

eventually be made into underwear for the

bride.

[102] The candy had a more ceremonial

function however. Most of it was to be shared by the women but a choice piece

would be offered to the bride by her future

mother-in-law.

[103] The bride would eat half

of it and return the rest to her mother-in-law to give to the groom to

be.

[104] This was a sign of her willingness

to share her life with him.

[105] The women

of the bride’s family (including the bride) would then repay the visit

with a social calling to the husband’s

family.

[106] If economically feasible, this

ritual would repeat several times, each time with a train of gifts from one

family to the other.

[107]This period was

likely the most functional of the pre-marriage festivities to the institution of

arranged marriages.

[108] While the rules

preventing the mixing of genders required that the women only interact with

other women, they also prevented the bride and groom from seeing each other

until their wedding night. Thus, this series of mass female visitation was the

second best way for the couple to gauge each other’s characters by getting

to know their respective families. As in any culture, it was considered

especially fortuitous for the bride and her mother-in-law to get along well

during these initial stages.

[109] If the

meetings did not go well, the bride’s family could still claim foreboding

dreams.

While these

visits were on going the fathers would hire the local imam to secure the

permission for the marriage from the local kadi and/or

imam.

[110] Permission was based on both the

religious and the secular law on appropriate degrees of familiar separation and

very likely served the important of function of keeping the central bureaucracy

fully informed of who in the powerful families was marrying

whom.

[111] When the marriage was approved, a

marriage contract was drawn up.

[112]

It’s primary purpose was to record the amount of the

dower.

[113] On the wedding day, the imam

would present the contract to both fathers who would sign after the imam first

asked the bride three times if she consented to the

marriage.

[114] The husband’s presence

was not required.

[115] The marriage

itself was considered to take place in the weeklong feast that occurred after

the signing of the marriage contract and the finances for the events

secured.

[116] This could take years and

often provided an excuse for a girl to mature a little more before she entered

into married life.

The week of

festivities followed a set schedule. On Monday the bride’s trousseau was

processed to her new quarters.

[117] This was

followed by a feasting of the bride with her female relatives and by a public

display of the trousseau. Any women could attend the viewing, and it was

considered very important for the bride’s father to suitably impress the

neighborhood women.

[118] Additionally, the

bride’s family would spend the evening setting up her new quarters so that

they would be ready for the couple to start their lives together at the end of

the week.

[119]On Tuesday the

bride and her guests went to the public

baths.

[120] There the bride would spend

hours being “soaped, pummeled, shampooed, scalded, and perfumed” by

the bath workers.

[121] “Her body hair

was removed with depilatory paste in accordance with the Hanafi law on decency

in women.”

[122] On Wednesday, the

bride received the groom’s female relatives and family

friends.

[123] The day was filled with

socializing and the evening spent applying henna to the bride’s hands,

feet and arms.

[124] This was the customary

entrance of the girl into womanhood and then formal good byes by the bride to

her female relations.

[125] Even if the bride

and her husband were going to live with her family, she was no longer under the

care of her father’s house, under the marriage contract she was now under

the care and protection of her husband first.

Thursday

morning was the formal preparation of the

bride.

[126] At this point her party

consisted of her mother, mother-in-law, close aunts of the couple and her

sisters.

[127] After being fully arrayed, she

formally approached her father who, speaking for the men of her family said

farewell to her and gave her the belt of the married women, signifying her

independence from her old family and subjugation to her

husbands.

[128] During this time, the groom

and his male relations processed to the bride’s family to claim the

bride.

[129] The groom passed through the

bridal party and was allowed a brief moment together with his wife, usually just

enough time to view each other for the first occasion and were then immediately

separated for separate feasting of all the women and all the men

involved.

[130] Interestingly, the women did

not wear their veils in his company “on the probably sound assumption that

he did not have eyes for them.”

[131]

Later the two groups would go to evening prayers and then the couple would be

left allow to enjoy dinner as their first meal

together.

[132] Consummation of the marriage

was expected on this night.

[133] A married

aunt or close to the bride would wait outside the bridal chamber all evening, in

case the bride needed to consult an experienced

adult.

[134] On Friday both families were

feasted and then guests sent on their way leaving the exhausted couple to start

married life together.

[135]If the bride

had been married before, the feasting and gift giving was minimalized with only

the legal and religious formalities still being strictly

followed.

[136] If the girl was marrying into

a polygamous household, the other wives were as a much a part of the wedding

festivities as her mother-in-law, though with lower

rank.

[137] The focus was on the young bride

and ensuring that her transition from girlhood to married life went smoothly,

with a great deal of support.

[138] Islam

encouraged widows to remarry quickly. The arranged marriage system worked to

help fulfill that, with the social networks of Ottoman women constantly updating

itself on who was recently widowed and how well off she was left by her husband.

Since her dowry was her property (though she had limits on her ability to

alienate it, beyond simple maintenance of herself and her household), her

economic worth would help to make up for any advancement in years. While

widows’ marriages were still largely arranged by their female relations,

they could count on having more influence, having been married once and knowing

what they wanted in a husband, and having been part of society, they had a sense

of potential men they wanted their family to target.

Arranged marriage was

accepted by girls and women as a matter of course – something all women

went through. Though the traditional disadvantages of arranged marriages, that

the couple would discover that their marriage partner was not all they had

imagined, applied to Ottoman arranged marriages. It was not until the advent of

widespread female education and Westernization in general in the late

19

th and early

20

th centuries that the institution

fell into decline.

[139] Arranged marriage

was one of many institutions that fell sharply under attack in the early

20

th century and was targeted by

reformers.

[140] Women, as well as men, found

it ridiculous that they first met their spouses on the wedding

night.

[141] A common reflection by reformers

being that one could examine produce in the market, even consult an expert

before a major purchase, but finding no common sense in the prevention of

examining a spouse before joining in

marriage.

[142] Conservatives

praised the system because not only did it encouraged the remarriage of widows,

but it helped to prevent spinsters as it was the girl’s family, not just

herself, attempting to marry her off.

[143]

When marriage was a community effort many more women found themselves married

and ideally cared for.

[144]

Polygamy

The Ottomans practiced polygamy.

They followed the standard Islamic limits of four full legal wives, as many

slaves as the husband could support and as many concubines as he

wanted.

[145] Sociologists of the empire

believe that polygamy mostly existed at the apex of society, with the wealthy

being the ones best able to afford multiple

wives.

[146] The most common reason a man

took a second wife was to procure sons.

[147]

Second wives were also often freed slaves. This had certain benefits. First

was that the husband could inspect his bride before he bought, freed and married

her. Secondly, because she had been trained as a slave, she was unlikely to

disturb the first wife’s mastery of the home.

This last benefit was considered

an import one because one method of maintaining domestic harmony in a polygamous

household was for the wives to follow a strict chain of command and the

etiquette that went with it.

[148] The lowest

wife was not without rights, however. “According to Ottoman custom, each

wife was supposed to have her husband’s amorous attentions once a week.

If a husband faltered in his attentions to a legal wife, she had the right to

complain and seek divorce.”

[149]

Another method of keeping the peace at home was to divide the house into

separate apartments for the different wives or even for the husband to simply

keep a house for each wife, if he was

able.

[150]

Divorce

Ottoman divorce was usually

controlled by tenets of the Hanafi Islamic law. In practice, the most common

method of divorce was by repudiation of the wife by the husband. To divorce a

wife, a “husband needed only to pronounce his wife divorced during the

time when she was canonically free from impurity, and then abastain from marital

relations with her for the next three months.... During these three months, he

could change his mind and take her back; otherwise ... the divorce became final

and irrevocable.”

[151] A husband could

remarry his ex-wife “only if she first married another man, consummated

the marriage, was divorced by him, and then observed a three month waiting

period.”

[152] If the wife turned out

to be pregnant during the three-month waiting period, there could be no divorce

until the child was born.

[153] Additionally

any man could simply make a statement of irrevocable

divorce.

[154] Hanafi law viewed this as

shameful but legal.

[155] Regardless of

method a man need never state grounds for

divorce.

[156] But a woman

did.

[157] Ottoman law provided three grounds

on which a wife could sue for divorce.

[158]

These were failure to financially provide for the wife, impotence or sexual

neglect and unproven accusations of infidelity made by the husband against the

wife in court.

[159] Additionally, Ottoman

courts would allow for divorce by mutual consent, but there was disagreement

among jurists if this meant the wife forfeited her

dowry.

[160] A wife’s divorce for cause

kept her dowry in tact.

[161] “In

addition, there was the provision that the wife was able to get a divorce by

virtue of her husband’s having delegated his right of divorce to her in

the marriage contract. Such a divorce was known as repudiation by

deputy.”

[162] Finally, a woman’s

family could secure a divorce cause for

her.

[163] Men most often

divorced wives for being childless. Infidelity does not seem to be a common

excuse for formal divorce procedures though, because the Ottomans worked so hard

to either keep women locked in the home or, even if she was free to leave the

house, her entire neighborhood and social network was dedicated to preserving

her virture.

[164] The neighborhood’s

imam was free to enter homes upon reliable reports that adultery was being

committed inside.

[165] As punishment, the

law required stoning for adultery or other kinds of unlawful intercourse

(

zina).

[166]

Since death removed the need for a formal divorce, this may explain the lack of

formal divorce action on this basis. Even if the state did not operate to

execute the adulterers, a husband had a right to kill his adulterous

wife.

[167] Ottoman law did not give her the

same right in return.

[168]ILLNESS AND

DEATH

Doctors, midwives and healers of all sorts enjoyed special status in

Ottoman society.

[1] Besides the useful

functions they served, healers were seen as users of magic and enjoy perceived

magical power over the world.

[170] Foreign

commentators on the Ottomans thought Turkish doctors were appallingly backwards

and inept.

[1] This was likely because of

widespread belief in superstition and because, until westernization, Turkish

doctors were trained on Galen and

Avicenna.

[1] These foreign commentators

remarked that citizens of the empire constantly asked them for cures and

medicines.

[1] This supposedly stemmed from a

wide spread belief that Westerners had an innate understanding of the physical

world.

[174] Western doctors still found it

difficult to actually examine female patients,

however.

[175] Many complained women would

only consent to be interviewed through a door held

ajar.

[176] Especially daring women might

allow their hands, arms and feet to be touched, but only through

gauze.

[177] The Ottomans were also

widespread believers in superstitious folk remedies and magic. These included:

“to pour lead, to extinguish fire, to pour sherbet, to cut spleen, to cut

jaundice, to expunge fear, to singe, to fumigate, to tie a fever ... to go

through some folk rite 40 times, to nail, and to read. In addition, letting and

leaching blood were also customary

remedies.”

[178] While most of these

cures had clear pre-Islamic origins, verses from the Koran were often read while

the cures were carried out. Often people from families that had long practiced

these cures carried them out.

[179] There was

both a belief in innate family ability and also in the hope that the

practitioner would be brought up in the family

art.

[180] Magic was not limited to

curative ends. A great deal of time and worry was spent on dealing with spirits

and spells. Many illnesses were thought to be caused by the malicious actions

of

jinns and

peris (loosely, genies and

fairies).

[181] The underlying disease could

either be treated itself or the spirits could be appeased. An Ottoman, thinking

himself prudent, would as often as not follow both courses of treatment. Thus

he would undertake certain magical rituals to appease these

spirits.

[182]Magic was also

used to influence others and protect oneself. “These spells were usually

cast by means of a

buyu bohcasi (packet

of charms) which ... ‘is composed of a number on incongruous objects, such

as human bones, hair, charcoal, earth, besides a portion of the intended

victim’s garment, etc., tied up in a

rag.’”

[183] The belief in magic

reached the highest levels of power. After the death of the Sultan Abdulmecit,

fifty of these charms were found stuffed into his

sofa.

[184] Influence aside, nothing was

more feared by Ottoman women than the ‘evil eye.’ Its intent is

malicious and its effect is to cause loss of health, life, beauty, affection,

wealth and very young children.

[185] The eye

did not require charms, so much as ill intent channeled by a bad expression and

malicious thoughts and comments.

[1]

Fumigations and repeating chanting of certain Koranic verses were the preferred

methods of riding oneself from its

effects.

[187] At the end of life, a good

Ottoman was expected to put his or her affairs in order and to put special

emphasis on the study of religion.

[188] The

Ottomans believed that as Muslims they would be tested in the afterlife on both

the value of their good works and on their understanding of their

faith.

[189] When a person

did pass, they were buried quickly, in accordance with Islamic

law.

[190] This meant massive community

involvement requiring a general neighborhood and family

meeting.

[191] At the meeting the community

assured the local imam of the worth of the

individual.

[1] Convinced that the person was

a good Muslim, the imam would then led the community in prayers designed to

release the person from their community to

God.

[193] The funeral was a chance for acts

of piety by the deceased family as displayed by massive alms

giving.

[1] Even if a tomb was built, the

deceased was always buried below ground.

[195]

Slavery

The Ottomans practiced slavery.

Initially a steppe people, the Ottomans took slaves as part of the spoils of

war. Many of these slaves were incorporated into the state structure, either as

recruits for the military and bureaucracy or as sources of revenue as the war

captives were sold into slavery in the Empire’s markets.

The Ottomans

also imported slaves. “Long before Istanbul became an Ottoman city, it

was a flourishing way station and market for the Caucasian slave trade.

Throughout the Middle Ages slaves were purchased in the Crimea and the ports of

the Taurus Peninsula for transport to

Mamluk

Egypt.”

[196] The Ottomans kept up this

important trade, especially after the empire stopped expanding, which resulted

in a massive decrease in war captives.

[197]

The Ottomans in Egypt also purchased Africans of all types and Alexandria was

the main center for the production and training of the black eunuchs that played

important roles in the administration of the Empire’s harems.

Like many of

the institutions the Ottomans inherited from their political forbearers, they

stream lined the institution of slavery and taxed it. The Ottoman government

normally took a fifth of the sale price of the slave as a

tax.

[198] This was collected from the

purchaser and was a prerequisite for the issuance of title to the

slave.

[199] This title would follow the

slave for life and if she was freed, the title was processed by a local

kadi and reissued to her as proof of

her freedom.

[200]The government

was not the only entity making money off of the slave trade. Professional slave

trainers, often women, would purchase young slaves, spend years training and

educating them and then sold their product at a profit: “Children of from

six to ten years of age are the most sought after by these connoisseurs, who pay

large prices for them in the expectation of receiving perhaps ten times that

amount when the girls are about

seventeen.”

[201] Many of these girls

would be sold off to the best families as wives for sons, or as concubines for

the master.

[202]Many slaves

were freed. “If a female slave became pregnant by a member of the

household, she could no longer be sold or given away, for she then had the legal

status of ‘mother of a child,’ and became free at her master’s

death.”

[203] Additionally, it was

considered a virtuous act to free slaves, especially Muslim ones. Many well to

do Turks would free some or all of their slaves in their

will.

[204] Slaves did not seem capable

purchasing their own freedom. Few slaves had no resources of their own and if

they did there were massive restrictions on the ability of slaves to alienate

them. A slave’s best hope for freedom was virtuous and pleasing service

to the master.

Pressure for

ending slavery came from the west. The British, in particular, objected and

tied a trade concessions and military assistance to clamping down first on the

trade of slaves and then on the existence of the institution

itself.

[2] The institution was finally

outlawed in 1908 by western inspired

reformers.

[2]

Regulation of Religions

This paper does not focus on the

various tenets of Islam or any other faith practiced in the Ottoman Empire,

though they all provided critical legal foundations for both the religious class

and for the

millet systems. But it is

important to address how the Ottomans dealt with and regulated the different

religions in their empire.

The Ottomans rightly saw Islam as a method of

controlling the populace because Islam is largely centered on orderly community

living. To that end, the Ottomans “sought to promote a state-sponsored

version of Islam, preached by men who were graduates of state-sponsored

[

medresse] and paid salaries from the

sultans’ coffers.”

[2] These men of

religion formed the core of what might be considered the empire’s Muslim

intelligentsia. They were its scientists, historians, and poets, as well as its

legal scholars. Their ethnic and social origins were as diverse as the empire

itself. As such, we might expect them to represent a diversity of outlooks.

But as a social and intellectual class, they held remarkable similar

world-views, undoubtedly molded, as hoped for by the state’s bureaucrats,

by their shared educational experience.

[208]

By ensuring that imams,

kadis, and the faculty of

medresse, were all state trained and

appointed, the Ottomans regulated and standardized Islam, in furtherance of

their goal of peace, justice and tax collection.

The Ottoman

approach to apostasy was determined case by case. What was controlling in each

case was the original affiliation of the apostate. It was forbidden for a

Muslim to abandon Islam. If he did, both he and the person who converted him

would be put to death.

[209] However, Muslim

peasants could move between different sects of Islam, though a true Ottoman was

a Sunni adherent to the Hanafi school. Though the Ottoman authorities did their

best to control all Islamic institutions by controlling important religious,

legal and educational appointments. Additionally the usual social opprobrium

applied to keep people within the traditions followed by their families.

Conversion to

Islam was encouraged, though, “there is no evidence of wide-scale forced

conversions ... with the possible exception of the

Albanians.”

[210] Instead, the Ottomans

provided incentives to convert. Islamization proceeded quickly in Christian

Analtolia as Greek and Armenian Christians accepted the faith of those who held

military and political power.

[211] One of

the oldest career paths for men, the military was only open to Muslims, with

important exceptions for some Balkan groups who accepted Ottoman suzerainty. As

such, Christian men embraced Islam as a way of getting into the military and out

of poverty.

[212] Christians might also

convert to Islam to take advantage of a quickie divorce. Newly converted men

could simply divorce their wives.

[213] Even

Christian women could obtain an easy divorce by converting to Islam, since it

was illegal for a non-Muslim man to be married to a Muslim

woman.

[214] The marriage was, in effect,

annulled. Additionally, women would convert in order to “claim a portion

of their fathers’ and/or husbands’

estates.”

[215] Islam also had

its own inherent appeal as a religion:

Islam’s

emotional and spiritual appeal to the sultan’s Christian subjects was

increased by the syncretistic interpretations which were being preached by the

wandering Sufi mendicants who visited the villages of Anatolia and later the

Balkans. Prominent among these were the adherents of the Bektaşi order who

blended elements of Christianity with Islam, retaining a special place for Jesus

and Mary and a fondness for wine while adding reverence for Ali. The retention

of Christian customs by the order must have seemed comforting and familiar to

the region’s Christian peasants, often physically remote from their own

clergy. Confirming this assumption, the strongholds of Bektaşi belief in

the Ottoman lands were found among the Albanians, Pomaks, and Bosnians –

the only Balkan peoples to apostatize in any great numbers – and in the

ranks of the Janissary corps, which was conscripted from the Christian subjects

of the sultans.

[216]The Balkans were the only area

conquered by the Ottomans that did not widely Islamize. The Ottomans may have

had an interest in keeping the Balkans Christian however, as it was the primary

source for the fabled and essential Janissaries

Non-Muslims were free to

leave their old traditions for new ones. Christians could join different

Christian sects or become Jews and Jews could become Christians. Complaints to

the Ottoman authorities of group members’ apostatizing largely went

unanswered by qadis who would usually repeat the teaching of Muhammad that

“unbelief is one

group.”

[217]

The Ottoman Military and Bureaucracy

In order to enforce their

poly-legal system, the Ottomans developed and deployed a massive military

complex. During the empire, the Ottoman’s armies were successful because

of the superb ability of the Ottomans to organize. Ottoman organizational

talent manifested itself in the military through the Janissary Corps.

The Janissaries

were slaves of the state. The Ottoman system of slave-soldiery had two very

important military advantages. First, because the Ottomans did not have to

advance officers on the basis of their familial wealth or power, a meritocracy

developed. Second, because the military was run through a meritocracy, the

assassination of a leading general was no huge setback as the Ottomans were able

to simply appoint the next best man. The Ottoman’s possession of an

assassination proof military led to no end of frustration for the Empire’s

enemies.

[218] Janissaries were recruited from

Christian populations under the control of the empire. Janissaries were most

commonly levied through a form of human taxation, called the

devşirme, of the children of the

Christian populations in the Balkans and Armenia, and to a much lesser extent,

in Egypt. The Janissaries had a Christian origin because Islam forbade the

enslavement of Muslims.

[219]

“Converted to Islam and taught Turkish, the most promising young slaves

were educated for rule in the Imperial Palace....The bulk of such slaves staffed

the Empire’s standing

forces.”

[220] “The janissaries

numbered 6,000 toward the end of Mohammed the Conqueror’s reign, close to

8,000 at the beginning of Suleiman’s reign, and 12,000 when he died in

1566. By 1609 the corps has burgeoned to

37,000.”

[221] The bulk of the professional

troops of the empire were cavalrymen known as

timarsiots:

In return for

military service they were granted incomes derived from agricultural tax

revenues collected from the provinces....By granting timars to their cavalrymen,

the Ottoman sultans solved the problem of maintaining a large military force

without huge outlays of cash. Since their economy suffered a chronic shortage

of precious metals, paying their troops with timars rather than with cash

relieved the central state treasury of an enormous burden. An added advantage

of the timar system was that the timariots, in addition to carrying out their

military duties on state campaigns, also performed important functions on the

local level in the provincial

administration.

[222] This seems to be a form of

Western European medieval feudalism, albeit with a much more advanced taxation

and record keeping system.

Members of the other two branches of

government were usually free-born Muslims who had access to education either by

being the sons of prominent families able to afford education in the home or in

the

medresse system or in the palace

schools. These men then obtained higher education at either the palace or in

the more preeminent

medrese

universities in Istanbul, Damascus, Baghdad or Alexandria. Those who would be

become bureaucrats initially transferred from the military (due to their

necessary organizational and record keeping skills) or from the among the more

talented kadi or teaching graduates of the religious

schools.

[223] Eventually, training for the

bureaucracy became centralized in the Imperial quarter of Istanbul and

bureaucrats learned though a master/apprentice system, usually while completing

a more generalized religious and literary

education.

[224] The elites of all three groups

were eligible for the very highest positions in the Sultan’s privy council

(divan). The make up of this group changed with the tastes of the ruling

sultan, but it almost always contained at least a Grand Vizier (who functioned

as a prime minister with more or less power depending on the other members of

the cabinet), the Seyhülislam (a chief interpreter of sharia and chief

overseer of the

medresse

system),

[225] the chancellor (a chief

interpreter of civil law and chief administrative secretary of the cabinet), the

chief treasurer, however many generals, admirals and military judges were needed

to adequately reflect the state of the Empire’s current campaigns and a

chief eunuch who oversaw the palace system and administered to the harem and the

extended royal family. Additionally, the Sultan’s mother always enjoyed a

great deal of access to her son regardless of the independence of his

personality.

[226] The presence of the Queen

Mother was usually felt in all cabinet meetings through her proxy, the chief

eunuch.

[227] Like all empires, the influence

of the Sultan would wax and wane depending on the strength of his personality

and those of his ministers.

[228] Under a

strong Sultan, the Empire would enjoy great military success as evidenced by the

conquest of Constantinople and the Nile. But the advantage of the bureaucracy

was that the central government could usually weather a bad sultan through the

force of sheer inertia or through the meritorious appointment and advancement of

able administrators. Proof of the Empire’s strength was the ability the

administration to cater to the needs of a massive and diverse imperial populace

– largely the result of a legal system that allowed communities to

self-rule within the limits of Islam.

Conclusion

The Ottomans ran an empire.

Instead of working to assimilate their subjects, the Ottomans instead choose to

coexist with their subjects as long as they remained passive. The Ottomans

strove to maintain their empire and their culture by living up to the standards

of the Circle of Equity and when they did, the Empire was strong and prosperous.

The flaw in their culture wasn’t internal; it was external. Faced with

the rise of Western Europe, the Ottomans only sought to maintain their own

status quo. Able to withstand any internal test, under its poly-legal system,

the Ottoman Empire fell to external influences beyond its control and was

replaced by secularized, pro-Western governments. These governments have not

succeeded nearly as well as the Ottomans in maintaining a diverse and dynamic

populace largely because they forced changed on all groups as opposed to

toleration and allowance for self-government.

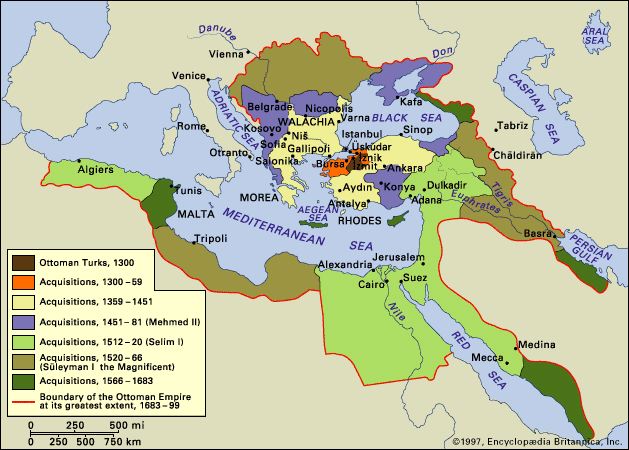

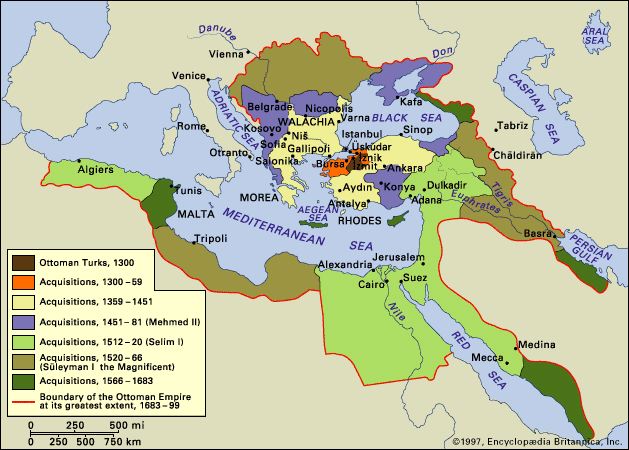

Appendix 1: Expansion Map

of the Ottoman Empire Appendix 2: Timeline

and List of

Rulers[229]

Appendix 2: Timeline

and List of

Rulers[229]

[1]

See

Fanny Davis, The Ottoman Lady

– A social History From 1718 to 1918 1-33 (1986). Being a black

African, however, relegated a person to the lowest Ottoman social classes. This

was ironclad with a few notable exceptions, such as the black eunuchs who

historically ran the royal household and administered to the royal

harem.

[2]

Davis,

supra note i at 70.

[3]

Norman Itzkowitz, Ottoman Empire and

Islamic Tradition 55

(1980).

[4]

Itzkowitz,

supra note iii at

56.

[6]

Id..

[7]

Bruce Masters, Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab Wolrd 11

(2001).

[8]

Masters,

supra note vii at p.

11.

[9]

Id.[10]

Id. at 60-65.

[11]

Id. at

20.

[12]

Id. at 21.

[13]

Id.[14]

Id. at

22.

[15]

Id.

[17]

Id.[18]

Id. at

22-23.

[19]

Id. at 23.

[20]

Wikipedia, Jizya. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jizya

[21]

Masters,

supra note vii at p.

32.

[22]

Id.[23]

Id.[24]

Id.

[25]

Id. at

31-37.

[26]

Id.[27]

Id.

[30]

Cornell H. Fleischer, Bureaucrat and Intellectual in the Ottoman Empire

197

(1986).

[31]

Id. at

198.

[32]

Id.[33]

Id. at 199.

[34]

Masters,

supra note vii at p.

33.

[35]

Id.[36]

Id.

[37]

Id. at

34.

[38]

Id.[39]

Id.[40]

Id.[41]

Id. at

33.

[42]

Id.

[43]

David F. Forte, Studies in Islamic Law

79 (1999).

[44]

Masters,

supra note vii at p. 52. The

Ottomans knew them to be revenue generators because many of Sephardic Jews spent

time in the Italian republics, learning the cutting edge business and banking

practices of the age. The Ottomans not only welcomed them because of their

expertese and capitol, but also because they provided skills the Ottomans

lacked.

[45]

Id. at

64.

[46]

Id.[47]

Id.[48]

Id. at 70.

[49]

Id. at

68.

[50]

Id. at

74-75.

[51]

Id. at

75.

[52]

Id.[53]

Id. at 74.

[56]

Itzkowitz,

supra note iii at p.

57.

[57]

See Masters,

supra note vii at p.

41-67.

[58]

Id. 70.

[61]

See “Courts” discussion

above.

[62]

Masters,

supra note vii at p.

33-34.

[63]

Id.

[64]

Id. at

33.

[65]

Id.[66]

Id.

[67]

Davis,

supra note i at p.

61.

[68]

Id.

[69]

Id.[70]

Id.[71]

Id.[72]

Id.

Kira were often minorities, usually

Jewish, but sometimes Armenian or Greek

Orthodox.

[73]

Id. at

62.

[74]

Id.

[75]

Id.[76]

Id. at

62.

[77]

Id.[78]

Id.[79]

Id.[80]

Id.[81]

Id.

[82]

Id. at

64.

[83]

Id.[84]

Id.[85]

Id.

[88]

Id.

[89]

Id.[90]

Id.[91]

Id.[92]

Id.

[93]

Id.[94]

Id.

[95]

Id. Here, the dowry was a vestige of

the bride-price paid by the nomadic Turks of Central Asia, fortified by the

injunction of Islam. No Muslim marriage was valid without a dowry. (Young,

Corps de droit, II, pp. 212, 219).

[96]

Id.[97]

Id.[98]

Id.[99]

Id.[100]

Id.

[101]

Id. at

66.

[102]

Id.[103]

Id.[104]

Id.[105]

Id.[106]

Id.[107]

Id.

[108]

Id.[109]

Id. at 65.

[110]

Id. at

66.

[111]

Id.[112]

Id.[113]

Id.[114]

Id.[115]

Id.

[117]

Id. at

68-69.

[118]

Id.[119]

Id.

[120]

Id. at

70.

[121]

Id.[122]

Id. at 70. This paste was commonly

made up of astringent herbs mixed with quicklime and perfumed with wood ashes.

This was called

ot. (White

Three Years, III, p.

305).

[123]

Id. at

72-73.

[124]

Id.[125]

Id.

[126]

Id. at

74.

[127]

Id.[128]

Id.[129]

Id. at

75.

[130]

Id.[131]

Id.[132]

Id.

[133]

Id. at

76.

[134]

Id. at

79.

[135]

Id. at 80.

[136]

Id. at

77.

[137]

Id. at

79.

[138]

Id. at 88.

[139]

Id. at

79.

[140]

Id.[141]

Id. at

78.

[142]

Id.

[143]

Id. at

79.

[144]

Id.

[145]

Id. at

92.

[146]

Id. at

87.

[147]

Id.

[148]

Id. at

92.

[149]

Id.

[150]

Id.

at 91. Polygamy ended with the empire. Having both lost it’s power base

and thus it’s source of wealth, the Turks banned polygamy with the

establishment of the republic. It is still practiced however, in the slums and

the more rural regions, though not commonly, and usually under the radar of the

authorities.

[151]

Id. at

119.

[152]

Id.[153]

Id.[154]

Id.[155]

Id.

[156]

Id.[157]

Id.[158]

Id.

[159]

Id.[160]

Id.[161]

Id.[162]

Id.

[163]

Id. at 123.

[164]

Id.[165]

Id.[166]

David F. Forte, Studies in Islamic Law

– Classical and Contemporary Application 81 (1999). The Ottomans

allowed some local variations on this rule however. In Istanbul, adulterers

were drowned in the

Bosphorus.

[167]

Davis,

supra note i at p.123.

[168]

Id.[1]

169

Id. at

265.

[170]

Id. at

267.

[1]171

Id. at

265.

[1]172

Id. at

266.

[1]173

Id. at

265.

[174]

Id.[175]

Id.[176]

Id.[177]

Id.

[178]

Id.

[179]

Id. at

267.

[180]

Id.

[183]

Id. at 268,

quoting Lady Fanny Blunt, The People of

Turkey, II, pp.

237-239.

[184]

Id.

[185]

Id.[1]186

Id.[187]

Id. at 268-69.

[190]

Id.[191]

Id. at

272.

[1]192

Id.[193]

Id.[1]194

Id.[195]

Id.

[196]

Id. at

99.

[197]

Id. at 99.

[198]

Id. at

105.

[199]

Id.[200]

Id.

205

Id. at

113.

[2]206

Id. at

114.

[2]

207

Masters, supra note vii at p.

27.

[210]

Id. at

27.

[211]

Id.[212]

Id.[213]

Supra – section on

divorce.

[214]

Masters,

supra note vii at p.

27.

[215]

Id.

[218]

See generally,

Anna Comnena, Alexiad

(1148).

[219]

Cornell H.Fleischer, Bureaucrat and

Intellectual in the Ottoman Empire 6

(1986).

[220]

Id.[221]

Itkowitz,

supra note iii p.

51.

[223]

Id. at

55-57.

[224]

Id. at 57.

[225]

Id. at

58.

[226]

Davis,

supra note 1 p.

11.

[227]

Id.

[228]

Itkowitz,

supra note iii p.

55.

[229]

Wikipedia, Ottoman Dynasty, available at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_sultan